Jim Jarmusch and Neil Young

Director

Jim Jarmusch’s intimate documentary about Neil Young and Crazy

Horse, Year

Of The Horse

spanned the band’s 28-year history, incorporating footage from

tours in 1976, '86 and their most recent '96 jaunt around America and

Europe.

"A Tale of 4 Guys Who Like To Rock"

"Year

Of The Horse" by Jim Jarmusch

The

Akron, Ohio-born Jarmusch, one of the pioneers of the American

independent film boom, is best known for his idiosyncratic movies

Stranger

Than Paradise,

Down

By Law

and Mystery

Train.

Music is a big element in all his films, and Jarmusch has cast rock

music personalities in his movies like Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and

Tom Waits.

The

director's relationship with Young began when the rocker did the

score for his last film, Dead

Man,

while Neil's own label, Vapor, released the soundtrack album.

Jarmusch also directed the video for the song “Big Time” from the

Neil Young and Crazy Horse record “Broken

Arrow.”

Year

Of The Horse

is about the band, Neil Young and Crazy Horse--which includes

longtime cohorts drummer/vocalist Ralph Molina, bassist/vocalist

Billy Talbot and guitarist/vocalist Frank “Poncho” Sampedro.

Former

Neil Young and Crazy Horse producer/arranger Jack Nitzsche is

represented in some still photos in the collection as well as a Crazy

Horse founding member, Danny Whitten.

The

live performances, along with the interviews and behind-the-scenes

footage, were filmed in Europe and the US during the '96 tour, with

some archival stuff from both the ’76 and ’86 treks. Most of the

performances were photographed in 16mm, but a large percentage was

captured on Super-8 film by L.A. Johnson and Jarmusch.

“But

mostly we used Super-8 because we love the way it looks—the raw

beauty of the material somehow corresponds to the particular quality

of the Horse’s music.”

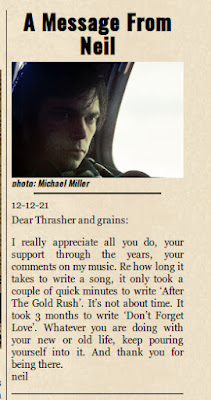

In

1998 Harvey

Kubernik interviewed director Jim Jarmusch in Los Angeles. Portions

were later published in Kubernik's 2006 book Hollywood

Shack Job: Rock Music in Film and on Your Screen.

Neil Young and Crazy Horse

Q:

How did your relationship with Neil Young formally begin?

Jim Jarmusch:

Neil and the band liked the results of the video I did for the song,

“Big Time,” which was shot entirely on Super-8 film in and around

Half Moon Bay, California. Neil particularly liked the rough look of

the Super-8. He called me up a little while later and said, “Listen,

we should do a longer film that looks and feels like the ‘Big Time’

video!” Neil liked the way we were such a small, portable little

crew.

Q:

What are you most proud or happy with after viewing and living with

this movie?

A:

I love the contradiction of Super-8 film on a big screen with music

that is recorded on 40-track digital Dolby... the combination of

high- tech sound with a real low-tech image. And somehow that

contradiction is very appropriate to this band, because they have

this huge transcendent sound that comes out of old amps and a very

raw kind of playing approach to the music. And somehow that raw

beauty and bigness and smallness together... I don’t know how to

explain it, but I think we captured that contradiction on film.

“Year

Of The Horse makes

it clear that the band's music comes from the whole band. Neil Young

is certainly their navigator, leading them into the soaring territory

of their songs, but Ralph, Poncho and Billy are anything but sidemen.

Together they create a singular sound that--in the same way John

Coltrane kept jazz alive and evolving with his group’s ‘sheets of

sounds’--keeps rock & roll alive through its emotional

connection to the musicians who are playing it. I wanted to shoot

Super-8 and then we covered the concerts that we shot in the house

with 16mm.

Ralph Molina Discussing Danny Whitten

Ralph Molina Discussing Danny Whitten

Q:

One of your film’s strong points is the fusion of archival 1976 and

1986 materials shot in 16mm and the utilization of photos blended

with the 1996 tours you and the crew captured.

A:

Neil had 16mm film material from 1976, and the ’86 footage was

“stolen” from Bernard Shakey’s film, done by Neil himself,

“Muddy Track.” The 1986 was high-8 video that Neil, and I guess

(arranger/ producer) David Briggs shot.

We

went that way partly because the small cameras allowed us to easily

shoot by ourselves, without a crew.

But

mostly we used Super-8 because we love the way it looks—the raw

beauty of the material somehow corresponds to the particular quality

of the Horse’s music.”

Q:

What did you notice about the '76 and '86 footage? I would imagine

even then the camera was mostly on Neil.

A:

I tried to keep the crews that shot our 16mm from doing that. Neil is

the lead singer, the lead guitar player and the songwriter, the front

man of the group.

Crazy

Horse tend to be overshadowed by, not by his own design but that’s

just the way it is. And one aspect of Year

Of The Horse

was to make those guys known as people a little bit, so we understand

them as a band, and not just as Neil Young’s backup, side

musicians.

I

began to realize they were a four-piece band when I started shooting

“Big Time.” I’ve always been a big fan of Neil,

particularly with Crazy Horse on album like Tonight’s

The Night or On The Beach. I

like the more dark, rock ‘n’ roll side of Neil. I think he’s a

great songwriter but Harvest

Moon

isn’t Ragged Glory for me, ya know.

I’m

a rock ‘n’ roller, so I never liked Crosby, Stills and Nash, for

example. It’s too sweet and light, and doesn’t speak to me. I

don’t respond to that stuff. So, I was always a fan of the Horse.

And I started realizing that sound comes from these guys and if you

were to replace any of the them you wouldn’t have that sound

anymore.

Neil Young and Crazy Horse

Photo by Henry Diltz, Courtesy of Gary Strobl at the Diltz Archive

Q:

Were Neil Young and Crazy Horse members cooperative interview

subjects?

A:

We were treated as part of their gang! We were in the same hotels and

given the room list. We were able to hang out with them anytime we

wanted—with or without a camera. We were very polite— we didn’t

barge in. They were really gracious. At one show in England, there

were 60,000 people there. Neil’s guys allowed myself and L.A.

Johnson on stage and let us film with total access. We’re not

supposed to get in Neil’s eyeline, because he gives 110% when he’s

on stage. He’s there to make music, not to make a movie. You get a

slightly different show when they play in small clubs, which they

love to do before they go out on tour. Those shows are amazing.

Q:

Were you always a Neil Young fan?

A:

I’ve been a big fan since I was a kid. I first heard the song

“Broken Arrow” by Buffalo Springfield, which was very visual and

dreamlike to me. I didn’t know what the lyrics meant, so I

invented my own scenario. After that, the next big thing that went

right into me was the first Crazy Horse record, Everybody

Knows This Is Nowhere.

So, I’ve been a big fan all along, but had never seen Neil live

until the late ’80s. The good stuff always held up. That’s why we

listen to Bach.

I

was listening constantly to Neil and Crazy Horse while I was writing

the script for Dead

Man,

then again during the shooting, which involved a great deal of

travel. Crazy Horse even performed in Sedona, Arizona during the

shooting period, and a large number of our crew attended the show.

I

wrote Dead

Man

in a little house in the Catskills with Neil’s music playing on a

boombox.

Q:

What did you learn about Crazy Horse's music, and Neil Young as a

writer/guitarist?

A:

He’s a real poet, but not in an extravagant way. I mean, he uses

very common language, but it becomes poetic in the economy. Things

are not over-explained. And what really kind of blew my mind was,

after I hung out with Neil at his ranch, I realized certain lyrics

that were very abstract to me I then saw, or had some insight into

what, literally, they were all about.

Q:

Tell me about the pre-production process.

A:

Filming is like going out and collecting material. It’s like taking

some guys and going out to a rock quarry and you bring back a big

chunk of marble. And then you look at it. Say you wanted to have a

sculpture of a horse and you bring back the model which you think is

the right size and shape, but then while you’re looking at it, it

tells you it should be a deer. Or a cow. You have to let the material

tell you what it wants to be. That’s the way I like to work.

There’s certainly the “Hitchcock School,” where you storyboard

everything. Hitchcock said himself that filming was incredibly boring

because it was just trying to translate this stuff on paper onto the

screen. But I like to be open to the things you can’t control. I

like to be open and bring something else ’cause... Neil is a master

of this. Often the best things you do are by accident or by mistake

or by things you didn’t plan properly. Things out of your control.

Q:

Were you impressed by the availability of film and video from earlier

tours that you were allowed to utilize in Year

Of The Horse?

A:

Well, it kind of threw me for a loop when I realized all that 1976

footage is a feature-length film. I keep tellin’ Neil, “Man, you

gotta make that into a feature length film. Then you’ll have ‘Muddy

Track’ from ’86, ‘Year Of The Horse’ from ’96 and this

other film from ’76.”

Q:

What did you observe about the growth of Crazy Horse and their

relationship with Neil over the years?

A:

They’ve become more pure and more loose at the same time. They are

more open to letting something take them away into the sky without

knowing the destination necessarily. I think they’re more

courageous in that way. And yet their music is wilder. It’s less

refined, less careful. Like, there’s Neil playing that solo from

’76 in “Like A Hurricane” that is a breathtakingly beautiful

guitar solo, but it’s very clean in a way. It’s a different kind

of purity. But then you cut to how far he’s gone to like this real

wild way-out-there stuff. He’s not afraid to go into dark terrain

and bring all that experience with him. They are warriors and they’ve

been in more battles and are more violent than ever. But they are

also stronger. I agree with Neil’s dad in the film when he says:

“Their music just seems to get better and better.”

Scott Young

(Writer, Neil's Dad)

Q:

It was also interesting to learn about the other members of Crazy

Horse. The candid interview segments really educated a lot of people

to a band that has played together for decades.

A:

They are not used to it. It’s like people have always gone by them

to get to Neil. And on one level they probably like that because they

are not thrown into the melee all the time. On another level, they

deserve, and know they deserve, respect for their contributions to

this “world’s greatest garage band,” or whatever you want to

call them.

#CrazyHorse4HOF

Q:

It’s not often we get to see and hear musicians run down their

individual histories around the age of 50 as they are sort of being

introduced to an audience for the first time.

A:

They’ve seen it all. These guys have had people die around them.

Tragic things. They’ve lived through really wild drug experiences

and they all survived. Not all of them, but these four.

It’s

like, when I worked on Dead

Man,

I spent a lot of time with native people in the States and Canada.

One old guy was saying, “In our culture, to be old is like getting

to go to the top of the mountain and looking out.” That’s a

value all the young people respect... a guy who has been able to look

out up there. Because in native culture, it’s very cool to be old,

you know. Their view is from a higher place. That’s very valuable

to those of us who are catching up to that, who are just starting out

our climb up the mountain.”

Jim Jarmusch & Neil Young

Harvey

Kubernik is the author of 20 books, including 2009’s Canyon

Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and

2014’s Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles

1956-1972. He

has also written titles on Leonard Cohen and Neil Young.

Sterling/Barnes

and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The

Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. In

2021

they wrote Jimi

Hendrix: Voodoo Child

for Sterling/Barnes and Noble.

Otherworld

Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s Docs

That Rock, Music That Matters.

His

writings are in several book anthologies, including, The

Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats

and Drinking

With Bukowski.

Harvey

wrote the liner notes to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s

Tapestry,

The Essential Carole King, Allen

Ginsberg’s Kaddish,

Elvis

Presley The ’68 Comeback Special, The Ramones’ End of the Century

and

Big

Brother & the Holding Company Captured Live at The Monterey

International Pop Festival.

On

October 16, 2023, ACC ART BOOKS LTD published THE

ROLLING STONES: ICONS.

312 pages. $75.00. Introduction is penned by Kubernik).

Also, see ESSAY: Neil Young’s Harvest at Age 50 by Harvey Kubernik.

More on Neil Young's "Year of the Horse" and Director Jim Jarmusch.

Also, see INTERVIEW: Jim Jarmusch & Neil Young - 1996.

Labels: #CrazyHorse4HOF, #DontSpookTheHorse, #SmellTheHorse, archives, concert, crazy horse, festival, film, interview, jim jarmusch, neil young, Neil Young and Crazy Horse, nya, tour

Human Highway

Human Highway

Concert Review of the Moment

Concert Review of the Moment

This Land is My Land

This Land is My Land

FREEDOM In A New Year

FREEDOM In A New Year

*Thanks Neil!*

*Thanks Neil!*

![[EFC Blue Ribbon - Free Speech Online]](http://www.thrasherswheat.org/gifs/free-speech.gif)

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young Pardon My Heart

Pardon My Heart

"We're The Ones

"We're The Ones  Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

This blog

This blog

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

What's So Funny About

What's So Funny About

Lots of intriguing discussion (both here and elsewhere) about band names, what it means to be “Crazy Horse”, does it matter, etc.

Here’s my perspective:

Let’s imagine a parallel universe where Bob Dylan really was killed in the legendary 1966 motorcycle accident.

(Or, if we want to be less morbid, let’s say he decided to retire from the music biz immediately after.)

The record company decide Bob is worth more to them alive than dead. And so they replace him with another singer/songwriter who strongly resembles him.

He wears a black wig, speaks in the drawl, writes compelling songs….

Nobody notices the difference.

(If this sounds incredible, consider the story of how Andy Warhol once sent an actor to replace himself on a speaking tour. Consider also how, in 2024, AI allows us to convincingly play with what is “real”. And of course, there’s the famous anecdote about Charlie Chaplin once entering a Charlie Chaplin lookalike contest and winning the prize for third place!).

More than 50 years later, this actor is still making Bob Dylan records and touring as a Bob Dylan.

The question is this:

Is he *really* Bob Dylan or not?

My answer is no…

and yes.

No, because it’s clearly not the Bob Dylan who made those classic '60s records for which the original was most famous.

And yes, because it *is* the guy who we’ve accepted as Bob Dylan for the last 5+ decades.

When we think of Bob Dylan, we think of the guy we’ve been listening to for most of our lives. At some point, the name “Bob Dylan” (essentially a brand name) came to stand for the persistent actor, not the fleeting original.

Back to the real world. Is it still Crazy Horse if one of the fundamental members of the group (“the glue… without him, it falls apart” as Niko Bolas once said about Poncho) is missing in action?

YES IT IS. Because clearly, Crazy Horse was around before Poncho Sampedro joined. And if the band can change line-ups once, it can do so again.

And NO, it isn’t. Because the Crazy Horse name is valuable because it stands for something magical — for the unique musical and psychological chemistry that has been nurtured between Neil, Poncho, Ralph and Billy for so many years. To deny that would be to deny the very thing that makes the band special.

If you drop a marshmallow into water, nothing much will happen. If you drop sodium into water, it will explode.

In music, as in chemistry, the specifics *matter*.

But of course, it’s not only sodium that reacts explosively with water. So do other alkali metals.

So the best way to view the 2024 version of Crazy Horse, I think, is as a band that is both separate *and* apart from the classic, longest-running Poncho lineup.

It’s still Crazy Horse, but at the same time, it’s a different Crazy Horse. With at least a partially-different dynamic, and very different chemistry.

Now, will it explode like sodium, or fizzle out? We don’t know until we try.

Seeing the 2024 version of the band as a new Crazy Horse (or at least, a musical cousin of previous versions) isn’t demeaning, but liberating. Because it stops unhelpful comparison with the past.

Listening to the new version of Over and Over, there surely might be the temptation to think “well, it’s pretty good, but obviously it’s not in the same league as earlier versions”. It needs to be heard in the context of 2024, not 1990 or 2012.

(An aside: The story of the new album, as far as one has so far been presented, isn't massively compelling. Perhaps that’s because the fundamentals are inherently less interesting. “Neil Young and Crazy Horse re-tread Ragged Glory at private gig for billionaire” is less compelling than “Neil Young and Crazy Horse play small bar in California and sell tickets at the door.”).

But a 2024 version of, say, Chevrolet? There’s no in-concert precedent to compare that to. So there’s the opportunity to define what it is while it is still growing, still finding its place in the world.

To sum up:

Why is seeing a band like Crazy Horse particularly special? Because the name stands for something. It stands for a very unique musical chemistry that has proved its worthiness on countless albums and countless tours. I don’t think we should gloss over that. And when Neil and Elliot speak in Year of the Horse about how special the relationship is between the four members of the band, they are doing so sincerely.

If these relationships don’t matter, if it’s just a bunch of guys backing Neil Young, then the band name would stand for nothing. To imply it’s the exact same band without Ralph Molina would be ridiculous, and the same applies to Poncho Sampedro — probably the most musically proficient member of the 1976-2013 lineup, as evidenced by his ability to thrive in various non-Crazy-Horse projects with Neil.

So thank you, Poncho Sampedro, for your contributions. You are missed, and the biggest compliment any of us can give is to truthfully say it clearly won’t be the same without you.

At the same time, life goes on. Previous masterpieces (or, more humbly, special moments) have already happened, and their legacy is assured.

But there are still new ones waiting to happen. And that’s both refreshing and inspiring, isn’t it?

Scotsman.