WHAT'S THAT SOUND?

THE COMPLETE ALBUMS

COLLECTION

by Buffalo Springfield

Courtesy of Rhino/WMG

(Click photo to enlarge)

Buffalo Springfield, Buffalo Springfield Again, and Last

Time Around - were newly remastered from the original analog

tapes under the auspices of Neil Young for a boxed set: WHAT'S THAT SOUND? THE COMPLETE ALBUMS

COLLECTION that shipped from

Rhino Records on June 29, 2018.

Here is a comprehensive, in-depth review of this Buffalo Springfield box by Harvey Kubernik.

In 1966 and ’67 Harvey Kubernik saw Buffalo Springfield in two of their

Southern California concerts and attended debut Neil Young solo concerts in the

region.

Thrasher's Wheat just recently published two highly popular articles by Kubernik:

Thanks Harvey! enjoy.

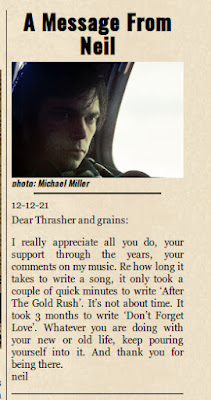

Buffalo Springfield @ Hollywood Bowl on April 29, 1967Photo by Henry Diltz. REVIEW: "WHAT'S THAT SOUND? Buffalo Springfield Box"

By Harvey Kubernik © 2018, 2020

Before playing its final show on May 5, 1968

at the Long Beach Sports Arena in Southern California, Buffalo Springfield

released three studio albums on ATCO during an intense, two-year creative

burst.

Those

albums - Buffalo Springfield, Buffalo Springfield Again, and Last

Time Around - have been newly remastered from the original analog

tapes under the auspices of Neil Young for a boxed set: WHAT'S THAT SOUND? THE COMPLETE ALBUMS

COLLECTION that shipped from

Rhino Records on June 29, 2018.

The

box set includes stereo mixes of the group’s three studio albums plus mono

mixes for Buffalo Springfield and Buffalo Springfield Again. There are

also CD and limited-edition vinyl sets.

I witnessed

Buffalo Springfield on stage during December 1966 at the Santa Monica Civic

Auditorium and The Hollywood Bowl in April 1967.

If

you dig Buffalo Springfield you might want to investigate my books Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic and The Music Of Laurel

Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In

Los Angeles 1956-1972. Plenty of Henry Diltz photos of the band members are

displayed in the pages around my text and interview subjects.

I’m

delighted Buffalo Springfield’s era-defining body of work will be heard and

discovered by new ears globally. I’m sure WHAT'S

THAT SOUND? THE COMPLETE ALBUMS COLLECTION coupled with my books will spur

additional interest for documentaries, television shows that will be produced as

well as subsequent titles still inspired by my teenage neighborhood. At Fairfax High School in West

Hollywood our Driver’s Education class was held in Laurel Canyon and the adjacent

Mt. Olympus region. Try learning how

to parallel park while “Nowadays Clancy

Can’t Even Sing” was on the AM radio station KHJ play list.

Buffalo Springfield’s three 1966-1968 albums were always debuted over

the Southern California airwaves before the rest of the world discovered

them. You really had to live in

Hollywood then to further understand and comprehend the initial impact of these

regionally-birthed discs and artwork design.

I’ve always felt the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, and then The Band, were

the joint Godfathers of Americana music.

WHAT'S

THAT SOUND? THE COMPLETE ALBUMS COLLECTION is a five-CD set for $39.98 and

on digital download and streaming services. High resolution streaming and

downloads are available through www.neilyoungarchives.com.

The albums

were released - for the first time ever - on 180-gram vinyl as part of a

limited-edition set of 5,000 copies for $114.98. The 5-LP box features the same

mono and stereo mixes as the CD set, presented in sleeves and gatefolds that

faithfully re-create the original releases.

WHAT'S THAT SOUND? THE COMPLETE ALBUMS

COLLECTION is available, this time around, chronologically and sonically improved

from the label’s 2001 Buffalo Springfield

Box Set product, but the fan boy

in me wishes the longer 9:00 minute version of “Bluebird” was included. It’s only found on a double vinyl LP Buffalo Springfield

package that was released in 1973.

So enjoy these Buffalo Springfield 2018

available recordings on compact disc and vinyl, as well as digital downloading,

before record labels like Rhino cease pressing up hard product and become

exclusively streaming services.

“In our

world of music in 2018,” posed author and film/music historian Jan Alan

Henderson, “has any new product stood the test of time that this Buffalo Springfield

box set will? Golden years, golden days as Mick Jagger and Keith Richards put

it, ‘Lost in the silk sheets of time.’”

“Sure, this was

one band who boasted within its rarefied ranks several musical characters of

superb pedigree indeed,” realizes Gary Pig Gold …who, for the record, may never

have visited Springfield but has been stranded in Buffalo several times. “Yet despite the fact that a failed Monkee and even

a couple Au Go Go Singers were on board, I have for a half-century-and-counting

insisted it was the presence of not one, but TWO certifiable Canadians that

truly gave this band its shine, its sharpness, and undoubtedly a big part of its unmistakable sound …even

on the stereo mixes.

“I speak, of course, of (a) Neil

Young, of whom little if anything need be added at this point, but especially of the (b) as in bassman –

and so much besides – Bruce

Palmer: Already by ’66 a veteran of more

spectacular Toronto-area rhythm ‘n’ Merseybeat combos than even young Neil

could’ve shook a Gretsch at, Bruce brought the incredibly innovative bottom he’d

already punched onto such woofer-blowing discs as Jack London & the

Sparrows’ ‘If You Don’t Want My Love’ (REQUIRED LISTENING, everyone!) to create

the beyond-solid foundations his Buffalo bandmates relied to create upon and,

yes, were expected to fly fully from.

“One could argue the Springfield was

never the same – some might even say never completely recovered from – the loss

of Palmer; not to mention the here today, maybe

here tomorrow ways of his fellow Canucklehead Neil. But all great art, even pop

(music) art, seems to burst best from turmoil, and that the Springfield always had in often self-defeating abundance.

They ‘burned’ briefly, but oh, so

brightly! As all the best herds, then and even now, seem to.

“They came, they played, and they crumbled.

Fifty-some-odd years gone. But still

as sound as ever.”

In 2001 I

interviewed Richie Furay about Buffalo Springfield. Sections of our conversation

first appeared in Goldmine and in my

2017 book, 1967 A Complete Rock Music

History of the Summer of Love.

“We were always comfortable singing someone

else’s song early on. The first album and some of the second, you can hear the

cohesiveness was a group effort, there was not the possessiveness of ‘this is

my song, this is my baby, I’m singing it because I wrote it.’ Early on there was this ‘what does this sound

like with you singing?’ I know we tried ‘Mr. Soul’ with everybody singing and

it sounded best with Neil. “The individual members brought their own take on

what was being presented to the song. We liked the Beatles with John and Paul

singing harmony. Stephen and I did a lot of that unison singing. That we picked

up from the Beatles but then there was a lot of experimentation”

Buffalo

Springfield then recorded their debut disc with managers/ producers Charlie Greene

and Brian Stone at Gold Star Studio in Hollywood, home of Phil Spector’s epic

musical productions. Owners Stan Ross and Dave Gold with engineer Larry Levine

with their landmark studio made pivotal contributions to Buffalo Springfield’s

studio endeavors. Ross trained Doc Siegel who engineered Buffalo Springfield with Tom May.

Stan Ross, along with his business

partner, technical wizard Dave Gold and Larry Levine made overt and subtle

sound design contributions to Phil Spector’s studio undertakings while jointly

constructing the ‘Wall of Sound’ which helped inform Buffalo Springfield.

The Gold Star studio clients of

Dave Gold and Stan Ross included Herb

Alpert & the Tijuana Brass, Sonny & Cher, Buffalo Springfield, Brian Wilson

with the Beach Boys, the Cascades, Iron Butterfly, Cher, the Cake, the

Chipmunks, Bob Dylan, Clydie King, Art

Garfunkel, Dick Dale, Bobby Darin, Minnie Ripperton, Johnny Burnette, Ray Ruff,

Thee Midniters, Donna Loren, the Sunrays, Mark and the Escorts, Jon & the

Nightriders, the Dillards, Tim Hardin, Beau Brummels, the Murmaids, Jackie De

Shannon, Led Zeppelin, Hoyt Axton, Duane Eddy, Margie Rayburn, Kim Fowley, the Runaways,

The Band, Go-Gos, Ramones, the Seeds, the Monkees, MFQ and the Turtles.

“Gold Star felt and sounded different than

any other L.A. studio,” explains the Turtles’ Howard Kaylan, who recorded “The

Story of Rock & Roll pop gem and other wonderful tunes like “Eleanor” there

in addition to their revolutionary L.P. The

Battle of the Bands produced by Chip Douglas.

“You could literally smell the tubes inside

the mixing board as they heated up. There was a richness to the sound that

Western and United, our usual studios, never had. Those two rooms sounded

‘clean’ while Gold Star felt fat and funky. Perhaps we were all reading too

much of the Spector legacy into the room, but I don't think so. Our recordings

from Gold Star always just sounded better to me. I miss that room,” lamented Kaylan,

whose band the Turtles sold 41 million records and had 9 Top Ten hits of their

own.

Gold Star

regulars Charlie Greene and Brian Stone were managers and producers, real show

biz operators, who represented Buffalo Springfield, Iron Butterfly, The Poor,

Bob Lind, The Cake, Dr. John, Jackie De Shannon and Sonny & Cher. “All I Really Want To Do” Cher's first solo

hit came out of the room, along with the duo’s “The Beat Goes On” and Sony

Bono’s solo masterpiece, “Laugh At Me.” Jackie De Shannon cut her Laurel Canyon LP there.

“Our

studio echo chamber gave it the wall of sound feel,” Stan Ross told me in a

2001 interview.

“Dave Gold

built the equipment and echo chamber and personally hand-crafted the acoustical

wall coating. We had so much fun with that echo chamber; it never sounded the

same way twice. Gold Star brought a feeling, an emotional feeling. Gold Star

was not a dead studio, but a live studio. The room was 30 X 40.”

“It was all

tubes. And when you have tubes, you have expansion and it doesn’t distort so

easy. We kept tubes on longer than anyone else. Because we understood that when

a kick drum kicks into a tube it’s not gonna distort. A tube can expand. The

microphones with tubes were better than the ones with out the tubes because if

you don’t have a tube and you hit heavy, suddenly it breaks ups. But when you

have a tube it’s warm and emotional. It gets bigger and it expands. It allows

for the impulse.

“Gold Star

brought a feeling, an emotional feeling. Gold Star was not a dead studio, but a

live studio. I’ve been in other studios that were ‘too hot,’ ‘too lively.’ Some

that sounded like card board boxes. ‘Too dead.’ Gold Star had enough that if

you snapped your fingers, or clapped your hands, you could actually hear it. So

if that’s the way your hands clapped, then your drum sound would be the same

kind of feel. Our echo chamber gave it

the wall of sound feel. It was smaller than most people knew.”

I asked Gold Star co-owner/engineer Stan

Ross about Buffalo Springfield sonic relationship to the Gold Star recording

studio.

“I was always

impressed by the songwriting abilities of the Buffalos,” he remarks. “Neil

Young, especially. The Buffalo Springfield was a self-contained group. A lot of

their stuff done as demos in studio A and B. with ‘Doc’ Siegel and myself with

the Buffalos. You won’t find a union contract on any of that stuff. Fun stuff,

kick-a-round time. Then track time and overdub time,” reflects Ross.

The band’s

Gold Star heritage can be heard in those 1966 and ’67 studio treks: Stills’

“Everydays,” plus Furay demos of “Words I Must Say,” “Nobody’s Fool,” Stills’

“So You’ve Got A Lover,” Young’s “Down To The Wire,” and another Stills’ song,

“My Angel.”

“Neil was

really a very personal friend of ours,” stressed Stan, “an appreciative man who

never forgot us over the years. Of all the guys in the group, Neil was the only

one who took care of Gold Star, especially Dave Gold.

“Dave did

Neil’s Trans album (along with

portions of Hawks & Doves). For

years Dave did all the mastering at Columbia that Neil did on his albums. He

made sure that Dave Gold would do all the lacquer mastering on his albums. No

one else. No other place. And if they wanted 15 pressing plants to have masters

Neil didn’t want prints made up from one master. He wanted Dave Gold to make 15

separate acetates. And to make sure it was done that way, Dave had to put a

number on each one he did that was a code between him and Neil.”

In 2009,

Neil Young finally made available his Archives

Vol. 1 multi-disc compilation. Song demos from Gold Star and both mono and

stereo mixes of Young-birthed Buffalo Springfield recordings, “Burned” and

“Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing” help populate the package.

Buffalo Springfield Again Side acetate label-1968

(Courtesy of Jeff Gold and Record Mecca)

Kirk Silsbee: I was compelled by the

sound of ‘Clancy' and it took me awhile to catch up to the depth of the lyrics,

and comprehend the role of Riche Furay’s performance on the tune's

success. It took years, matter of fact. Even though I felt it on a

visceral level, I couldn't articulate what it was doing, and what it was doing

to me.

“The Springfield had three good writers, but

Neil cranked out the bulk of the band’s material. It was very smart to

give those vocals to Richie Furay. Neil had an odd voice, with

a haunted edge to it and lacking warmth. Richie's voice, on the

other hand, was far more engaging and even sweet, in the best sense of the

word. But listen to ‘Clancy'--it’s quite a poignant vocal performance.

The lyrics on ‘Clancy’ are emotionally torturous, which seemed to be

Neil’s stock and trade at that time. Around the same time he cut ‘Down to

the Wire’ at Gold Star; it surfaced later on Neil’s Decade. I love

all three versions, and I respect the fact that Neil was experimenting, taking

chances. ‘Okay--let Stephen song it one time; let Richie try it, and the third

time I’ll sing it. But let's play with the crazy psychedelic overlay

holocaust stuff.’”

Richie

Furay: The band was that first album and it was never

captured again. That album represented the five of us together in the studio.

After that it started to fall apart. It got worse with the next two albums.

There were a lot of people being used other than the five of us.”

James Cushing: The musical and lyrical news from Buffalo Springfield was very,

very different from the kind of information you would get from the Beach Boys.

The Beach Boys were saying that Los Angeles and the Southern California region

was heaven. On the first single, ‘For What It's Worth,’ Stephen Stills and

Buffalo Springfield were saying that Los Angeles was a place where you had to

be extremely careful. What was powerful about that song was

partially the voice of Stephen Stills and partly that minimalist guitar from

Neil Young. From the first album, Neil Young’s folky, anti-virtuoso

concept was fully formed. You hit just the right notes and let them ring out.

“Neil also voices chords in a unique way I don’t have the

technical vocabulary to describe, but there’s something about the way he voices

a chord versus the way Stephen Stills voices a chord. Maybe he likes to use

different intervals. Maybe he likes to hit the notes in a different way.

Together they are collaborative and competitive.

“As far as their sense of rhythm goes, I

think Neil’s sense of rhythm is much more rooted in folk strums and strings.

Stills is actually more rhythmically interesting than Neil. But one of the

reasons that Stills sounds so interesting is that Neil always gives him that support.

Stills' strengths are enhanced by Neil’s strengths.

“The

first album is not an unqualified success, though. ‘Flying on the Ground Is

Wrong’ sounds a little tricked out today. The lyrics show Neil Young trying a

little bit too hard to show that he’s clever. It's the sort of mistake that

young writers make. But ‘Nowadays Clancy Can't Even Sing’ makes up for

it. What I loved then and now about "Clancy" is its combination

of country-western directness and lyrical elusiveness. Lines in ‘Clancy’

have stayed with me for multiple decades, like lines in Dylan’s ‘Queen Jane

Approximately,’ and in both cases, I would have a terrible time explaining

what they mean. But intuitively and experimentally, I feel they illuminate

moments of experience in the way only the best poetry does.”

Kirk

Silsbee: The

Buffalo Springfield is tied to the fabric of the Hollywood Renaissance in a

special way. So often the bands gestated in the suburbs or traveled

outright from different far-flung cities to try their luck in the Big Leagues.

But the Springfield was a mix of people from different cities who came

together in Hollywood like spontaneous combustion. Can you think of

another band that has a creation myth like the Springfield? People are

still debating the precise details nearly sixty years after the fact.

Talent was never an issue; the problem for the Springfield was finding a

center where all of the artistic visions could peacefully coexist.

“Buffalo Springfield's Hollywood was a

world with four AM radio rock stations and a full time country

station. Teen magazines like The KRLA Beat, Hit

Parader, and TeenSet were on the verge of

publications trying to seriously address the music. Unfortunately, the

writers at the time didn’t always have the tools. The writers were

basically teenage fans with bylines. You look at those pieces now and

there’s just so much missing in them--the gee whiz quotient is pretty high.

“In the

first stages of the Springfield, Neil Young was conscious of wardrobe, image,

clothing. He liked the buckskins that Genie the Tailor made for him or

the faux Indian get-ups he could get at Western Costume

on Melrose. But then, each guy in the band went his own sartorial

way. Fortunately, there was never an attempt to put them in band suits; they

all had their own sense of style. Stills was often seen in a hip jacket

and tie; he went to Sy Devore and Beau Gentry. You'd see

Richie with a thrift store jacket and open shirt, next to Dewey, in

a velour pullover. Neil had his buckskin jackets, one with very

long fringe coming off of the arms; I believe he slipped it on like a poncho.

But fashion? No. Look at Love’s first album--that’s a fashion

statement.

“Even though it broke up on the cusp on underground FM rock radio,

Buffalo Springfield became an FM band. Aside from 'For What It's Worth,'

it wasn't a hit-record band. There was no FM in late ’66, but the

Springfield eventually got a lot of FM airplay.

“In

the year-and-a-half up to June 1967--when the format changed--there was no

station like KBLA. It was our pirate radio, and it set the stage for

the FM revolution to come. Beginning in last part of

1965, KBLA made the bold choice to acknowledge the albums coming from

these L.A. bands--not just the one or two hit songs pressed as 45s. This

was the period when rock was becoming an art form, and albums had non-hit

material that was often more fascinating than their hits. For the first

time, the album cuts actually had merit on their own; they weren't just filler.

And even though they weren’t getting played

elsewhere, Burbank's KBLA gave them parity with hit records.

That was revolutionary as far as I was concerned. ‘Clancy’ got

plenty of airplay on KHJ, a Drake-Chenault chain Boss Radio format,

and the station always supported Buffalo Springfield.

“In ’67, Dewey Martin and Neil Young

knocked on the back door of KFWB on Hollywood Boulevard and handed

deejay Dave Diamond an acetate of ‘Blue Bird’ to spin. So often in those

days you had one or two creative minds in a band; the rest usually kept up the

best they could. No so the Springfield. I don’t want to say ‘super group’ but

their collective talent had a tremendous range of expression.”

Rodney

Bingenheimer (Deejay): Greene and Stone were managers and producers, real show biz

operators, who represented Iron Butterfly, the Poor, Bob Lind, the Cake, Dr.

John, Jackie De Shannon, Sonny & Cher and Buffalo Springfield. I loved Gold

Star. I played one of the tambourines on Sony & Cher’s session for ‘Bang

Bang (My Baby Shot Me Down).’ At Gold Star everyone was wearing Levis and some

buckskin things, Fairchild moccasins. Dewey Martin liked to wear velours.

“Charlie and Brian were always at Gold

Star. I loved Buffalo Springfield. I always saw them at the Whisky a Go Go. It

was a ‘jangly’ folk sound. Sort of ‘Byrdsy’ in a way. ‘Country Byrds.’ They

would gig all over Hollywood: The Troubadour, Hullabaloo. Charlie and Brian

were really good behind the board. I liked them as record producers.”

Henry Diltz (Photographer): I went to Gold Star in June 1966 when they

were doing their debut album. I had recorded there before with the MFQ and Phil

Spector. I was in the rom in July when Buffalo Springfield cut ‘Nowadays Clancy

Can’t Even Sing.’ I met their dog Clancy in the parking lot.”

Rodney Bingenheimer:

I liked the first album. ‘Clancy’ was incredible. ‘Down To the Wire.’ Stan Ross

was all over the place getting it together. Stan and Larry (Levine) were more

than engineers. They knew what they were doing as if they were the producers.

The first album didn’t really capture the Buffalo Springfield on stage. Just a

little.

“I later did go to Columbia studios and saw

the mix of ‘For What It’s Worth’ happening. Pretty amazing. I knew it was going to be a big hit.”

James Cushing: (Deejay): What was

powerful about that song was partially the voice of Stephen Stills and partly

that minimalist guitar from Neil Young. From the first album, Neil

Young’s quirky, anti-virtuoso concept was fully formed. You hit just the right

notes and let them ring out. Neil also voices chords in a unique way I don’t

have the technical vocabulary to describe, but there’s something about the way

he voices a chord versus the way Stephen Stills voices a chord. Maybe he likes

to use different intervals. Maybe he likes to hit the notes in a different way.

Together they are collaborative and competitive. As far as their sense of rhythm goes, I think

Neil’s sense of rhythm is much more rooted in folk strums and strings. Stills

is actually more rhythmically interesting than Neil. But one of the reasons

that Stills sounds so interesting is that Neil always gives him that support.

Stills' strengths are enhanced by Neil’s strengths.

It wasn't until 1969 that the Guess Who achieved global acclaim with their first million seller single, “These Eyes.” The Burton Cummings-Randy Bachman songwriting team turned out three more million-selling tunes, “Laughing,” “No Time” and “American Women.”

"You must understand the Winnipeg psyche," Burton Cummings explained to me in 1974 in an article published in Melody Maker. "It's not like growing up in London, Los Angeles, New York, or Chicago. Winnipeg is a small town. It's the prairies in Canada. I was locked up there so long that's all I wrote about.

"Neil Young was in a group (the Squires in March 1965) with (our drummer) Garry Peterson’s brother Randy.”

The group first tried to gain American recognition in 1967. Guitarist Randy Bachman suggested recording Young’s “Flying On The Ground Is Wrong. Buffalo Springfield’s album was already out by then but Neil played the guys in the Guess Who an acetate of it in Christmas 1966 when he came back to Winnipeg to visit his mom. Neil spun the LP for Randy. The Guess Who then recorded ‘Flying On The Ground Is Wrong” and two other tracks in London at IBC studios, March 3, 1967.

"We went to England to do an album and tour. The record deal and tour fell through. We were £25,000 in debt."

Young was absolutely thrilled that his old pals in the Guess Who recorded one of his songs. It was the first cover of a Neil Young composition.

James

Cushing: “Flying on the Ground Is Wrong.” The tune is a

little tricked out. It sounds there like Neil Young is trying a little bit too

hard to show that he’s clever. And that’s the sort of mistake that young

writers make. That’s the mistake I made in my early poems was trying to get

attention to how smart I was.

Kirk Silsbee: “Flying On The Ground is Wrong" is one of the best post-Dylan songs of its time. In just three stanzas Neil brilliantly paints a picture of emotional disconnection and missed opportunity. Even though there's an inviting girl in front of him, nothing is quite right in his world. It’s very poignant and you can’t minimize Richie Furay’s contribution to the success of the recording. 'Burned' is also on the debut album. The quality and sheer volume of Neil's songs during his Springfield tenure is, if not overwhelming, extremely impressive.”

John

Hartmann:

In 1965 and ’66 I had been at The William Morris Agency and I would get people

on TV to sell music. Then Shindig!

came along and that was my show. And I

signed Jack Good to William Morris. When

I was standing in the wings watching the Rolling Stones perform on stage I

encountered Sony Bono and then signed Sony & Cher and signed them to

William Morris.

“Charlie

Greene called me up one day and mentioned he had ‘America’s answer to the

Beatles, Buffalo Springfield.’ Charlie Greene, Brian Stone, myself and Skip

Taylor then drove to San Diego to see the act. I was in after the first

song. Because when Skip and I had come

back from San Francisco we started a thing called Stampede. And we’ll break

Buffalo Springfield. It would have been the first Bonnaroo Music and Arts

Festival. It didn’t happen. I booked Buffalo on The Hollywood Palace television show.”

Dickie Davis: When Buffalo did The

Hollywood Palace Neil was great, by the way. He came down there with that

mean look on his face and stole it. I got to play with Neil on the show when he

was doing his greatest solo. My back to the camera. Bruce wasn’t available and

I sat in. Bruce never looked at the camera. You would say, ‘Bruce you gotta

turn around and smile.’ And that would piss him off and he would just face his

amplifier. A phenomenal bassist.

“I thought

Neil was a poet who can write pop songs. So was Dylan and Paul Simon. I was a

poet myself. It was like a country song that had just grown a little. And Neil

did his own stuff like ‘Burned.. And nobody wanted Neil to sing. When I started

hearing all his material I started to realize I might have it wrong. That I had

seen a band, a group, and the focus. I wanted the band to succeed as a band.

And I put all of my energy into that.

“Neil Young

understood wardrobe but everybody showed up in whatever they wanted to show up

in. I have a photo of Neil sitting on top of a trash can with his Indian garb

on like he was Indian scouting. What Neil liked about the fringe jacket was how

it went all crazy when he played guitar. He liked flailing fringe. And it was a

great visual image, you know. As far as band clothing, there was a

{charge}account at DeVoss which I believe the group paid for whoever bought

there.

“While we

were in San Francisco playing the Filmore West, I had to borrow 300 bucks from

my parents to keep us alive, feed the band and do laundry,

“We were in

San Francisco and playing shows at The Ark with Moby Grape. I’m back in town. The night before I’m

driving home and by Pandora’s Box I make a right on Crescent Hights to go on

Fountain and in the parking lot are maybe 40 school buses and a huge bunch of

L.A. sheriffs or cops or whatever in that parking lot. The police presence was

military. It was like really oppressive. And I wondered ‘what the fuck?’ It

hadn’t happened yet and I went home. Outside Pandora’s Box. Somebody jumped up

on a bus. They (the sheriffs) moved in. A lot of kids had been arrested

(earlier) for curfew (violation). You gotta remember on the strip the political

pressure on the Sheriff’s department in Hollywood was to get rid of these long

haired freaks. Stephen wrote the song ‘For What It’s Worth.’

“You know,

Neil had a run in with the cops on Sunset Boulevard in front of the Whisky. It

started with me. I had come down to put some money in my (parking) meter that

had expired. And I was literally running to put some money in the meter and the

cop pulled up right beside me. ‘Come here!’ ‘Give me one second.’ And I ran to

the meter to put the money in. They grabbed me, slammed me down on the hood of

the car, kicked my legs apart. I mean, I still have bruises. I think they were

gonna take me in for a traffic or parking violation or something. They were

rough for nothing. People went and told Neil after he drove up to the Whisky in

his Corvette. Buffalo Springfield were rehearsing at the Whisky. They came out

and they started saying things like, ‘let him go,’ or ‘where are you taking

him?’

“So they ran

a make on everybody and got Neil on a warrant. Parking tickets. They let me

go. So they took Neil in and mistreated

him badly at the West Hollywood Station. He had long hair in 1966. When I

picked Neil up after that Neil was a changed person in terms of confidence.

Neil was shaken to his core. He was frightened. Neil told me they said, ‘Let’s

go feed the animals.’ He was bruised while in there.

“‘Mr. Soul’

was written partially about that. I remember first hearing ‘Mr. Soul’ at a club

in Beverly Hills called The Daisy. We rehearsed there but don’t know if we

played there. Neil always had that growling guitar. And I had seen Neil’s anger

coming (in that song).

“He was noticeably

different after that. And I’m telling you, whenever we went anywhere Neil

didn’t want to be out on the street. He wanted to go in back doors. It took a

while. That shook Neil, I think. It shook me and a lot of us. If you went into

some places like Googie’s with long hair they wouldn’t let you in. The people

who were making money on the Sunset Strip did not want the hippies.

“The Buffalo

first stayed at the Hollywood Center Motel and then Neil had his apartment in

Hollywood at Commodore Gardens, later at his place in Laurel Canyon. 8451 Utica

Drive. Or he had people who would bring him to gigs. His friends Donna (Port)

and Vicki (Cavaleri).”

Peter

Lewis: Moby Grape played with Buffalo Springfield in November

1966 at The Ark, a dry docked ferry boat with a slanted dance floor in

Sausalito after they played the Fillmore.

Skip (Spence) our drummer and Bruce (Palmer) Buffalo Springfield’s

bassist were friends. Neil and Stephen went and talked to the guy who ran the

place. I saw him point to me. ‘We’re Neil Young and Stephen Stills and we’re in

the Buffalo Springfield. We’ve come to see Moby Grape. I guess you’re one of

the band members.’ ‘Yes.’ So they broke out their guitars. I think they were

Martins and I had a Guild D 225. The first thing I noticed was how good Stephen

Stills was right away. We spent three or four hours together and I was alone

with them for a while playing songs and listening to their songs. They had one

good song after another. The caliber of the tunes.

“Neil played

‘Mr. Soul’ but it was in a D tuning. Skippy used to do that. I asked Neil why

he did that in D. ‘Because it changes the scale shape on the bottom. Neil used

this D tuning on ‘Mr. Soul’ which allowed him to use this open chord, you know,

like the head stock nut instead of having to bar it. Right away I was struck

away by the way they would kind of alter the thing. Everybody was trying to

sound different in those days. Like, the Lovin’ Spoonful did not sound like the

Byrds. The rest of their band showed up and we played. And they were like,

‘Fuck!’ We just started trading sets at the Ark. Hanging together for a week or

so. Stephen went to military school and

so did I. We had a brotherly type of

thing, you know. If Stephen was trying to teach you a song and you didn’t know

a chord, ‘you stupid fucker!’ I remember him saying that to me. I knew music

theory. I learned it at school. But they don’t tell you how chord chemistry

works.

“The bands

were a lot alike. Three guitar lineup. There might have been a competitive

vibe. Where Stephen was really competitive. So if he sees you do something he

likes he’ll do it the next day better than you. So there was that. And Neil

struck me as a guy doing his own thing. He has that sense of self. From as much

as I know Neil, he has a sense of being unique that kind of separates him. Just

a pre-conception of himself. It’s not an ego thing. First of all, he has, or

had epilepsy. I saw him have a seizure one time in the control booth at a

recording studio. And they had to stick something in his mouth. And, Stephen’s

you know, ‘he’s just faking.’ (laughs). So, like in a way I identified with

him. Just being a movie star’s kid [Oscar-winning actress and television star,

Loretta Young] growing up you kind of get left by yourself. In a way, Neil

struck me like that.

“His ‘Mr.

Soul’ is not like ‘For What it’s Worth,’ a kind of gather the troops kind of

thing. ‘Mr. Soul’ is like what it means to be nuts. I was struck by that right

away. And his ability to sort of write a whole song in your head, have the

bridge and everything and all these chords. I was struck by the genius of his

tunes. “We played the Ark all the time every night.

We had that really good first record because we kept the songs that everybody

kind of dug a lot.”

“Buffalo Springfield had a kinetic thing. They

were like a family. Stephen and Neil were always kind of vying for position.

But that worked out. Richie was kind of between them with a high voice. He was

the one between the two other guys being the wings and Richie being the

fuselage of an airplane. The balance of things or trying to control.

“I think

after the Ark they changed their style. They were doing more like a kind of

sing and songy deal. I don’t think Neil was affected by it in a way. {bassist}

Bob Mosely was the guy {in Moby Grape} they were stunned by, you know. They

wanted to get him out of Moby Grape and into Buffalo Springfield. They had him

come down and audition. Bob’s story was

of course, they didn’t want some guy singing and doing his own songs.

They just wanted what Bob could do on his instrument.”

The Stephen

Stills’ composition “For What It’s Worth” was partially influenced or at least

informed by two tunes in Moby Grape’s live repertoire. Jerry Miller and Don

Stevenson’s “Murder In My Heart For The Judge,” (both utilizing the exact

E-Major/A-major, folk-soul chord progression with a shuffle beat), and an

unreleased Lewis offering, “Stop” (Stop!, listen to the music’).

Peter

Lewis: Buffalo Springfield did hear us play ‘Stop!’ and

‘Murder In My Heart’ at the Ark, Later

after they came back to San Francisco and played the Avalon Ballroom, Stephen

said to me, ‘You know, we just recorded this song (‘For What It’s Worth’) and

after it was done, you know, I flashed on where it came from.’ I said, ‘who

cares? ‘It was cool. There was nothing to get into litigation about, man.

“We lived in

Mill Valley. I had a great time with Neil and Stephen in Mosley’s apartment

playing each other songs. Bob wasn’t married and you could go over to his

place. Somebody had some pot. It wasn’t very good in those days. All bunk. Like

powder.

“There was a

point where they took us to meet (Ahmet) Ertegun down in L.A. It was like

sitting down, cross-legged on the floor, and Ahmet smoked a joint and passed it

around. What Neil and Stephen we’re trying to say, and I kind of knew this

about show business, you better be able to call the guy that owns the company

and get a call back.’ Columbia is not like that. Buffalo Springfield really

wanted us to make it. That’s what I remember. We signed with Columbia.”

The group spent the first half of 1967

making Buffalo Springfield Again, which was the first album to

feature songs written by Furay ("A Child's Claim To Fame.") Stills

and Young both contributed some classics with "Bluebird" and

"Rock And Roll Woman" from Stills, and "Mr. Soul" and Young’s

"Expecting To Fly."

In 2014, I interviewed legendary record

producer and manager, Denny Bruce. Portions later were published in my book Neil Young: Heart of Gold.

Denny

Bruce: In 1966 I first met Neil

when he was living in an apartment at the Commodore Gardens in Hollywood. I saw

Buffalo Springfield play all the local clubs. The Whisky, Gazzarri’s and

smaller places. After performing Neil would go to his apartment still wide

awake and write songs. Neil

and I had a casual friendship and he was a true fan of music. Neil was always

interested in my opinion about all matters of things pop.

“One night at the Greene and Stone office

I was talking to Neil. Because he basically is a shy person, I introduced Neil

to Jack Nitzsche. Neil also indicated to

us that he wanted to create a musical and lyrical mix of the Rolling Stones and

Dylan.

“In 1967, Neil and the band left Gold Star

to do Buffalo Springfield Again. And

Neil finally saying, ‘I’m gonna use some other players.’ I did attend one of

the marathon session dates for ‘Expecting to Fly.’ Jim Gordon on drums and Don

Randi on keyboards. All good players who Jack picked. He said to Neil, ‘This is

gonna be a good solo deal. Not a Buffalo Springfield record.’ And Neil said,

‘Good. I don’t see them on this record.’ I said, ‘Not even Dewey?’ And Neil

shrieked ‘No!’

“Jack really believed in Neil’s music. And

Jack knew Neil would eventually become a solo star. He knew he wasn’t meant to

be in a band.”

Don

Randi (Keyboardist): Jack Nitzsche called me to play keyboard on

some dates in 1967 at Sunset Sound. I picked out the piano for the studio. A guy who had a store on Beverly Blvd. When I

walked into Sunset Sound I didn’t realize it was for Buffalo Springfield. I thought it was for a Neil Young (solo)

album, ‘cause that is what he was supposed to be breaking away from and going

on his own. Hal Blaine and Jim Horn are on the track. I played piano and organ.

When Jack and Neil asked me to play on the end part of ‘Broken Arrow’ they were

both waiving me on to keep playing. I kept lookin’ up at them, ‘are you ever

gonna tell me to stop?’

“Let me tell

you something. Jack really enjoyed working with Neil. This goes as well to

‘Expecting to Fly.’ Russ Titelman, Carole Kaye and Jim Gordon are on it. Piano and harpsichord. I had some little head

chart arrangement to work from and another of the tunes might have been

sketched. It was pretty wide open with the chord changes. And all you had to do

was hear Neil sing it down with an acoustic guitar and you sat there, ‘Oh my

goodness.’ He was so talented. And Jack enjoyed Neil and to be with him because

Neil was so talented. Jack and Neil were a team and had a mutual admiration

society. And they liked each other and recording with them was easy. Neil wrote

cinematically and Jack arranged his own records cinematically. He did movie

scores as early as 1965.

“But Neil

took it a step further with his lyrics. I was real busy with session work in

those days. In one week I did 26 sessions. I’m on Love’s Forever Changes and Neil was around a bit on that album. (Red

Telephone?). Jack and Neil were tight. 1967, ’68.

“Jack and I

never judged artists by their voices. To me it didn’t matter ‘cause I loved the

music so much. And Neil was able to sell it. There are some people you can’t

stand them on record until you see them live. And once you see them live you

can understand their records. That doesn’t happen a lot. But it does happen.

“And you

gotta remember, by 1967 some of the recording studios in town, like Columbia

and Sunset Sound now had 8-track tape machines. When it happened I welcomed it

but all I thought at that point, ‘well the studios are gonna get rich now.’

Because nobody is gonna know how to mix this stuff. And when they mix it

they’re gonna have to come down to mono because nobody has got stereos to play

it on. And guys like Jack and Neil with 8-track now had more options and tracks

to fill. But what makes me wonder how did Brian (Wilson) do it on 4-track?

(laughs).

“Brian

learned how the game was played. Neil knew it earlier. And I would love to have

said how big Neil was gonna get. I don’t think he realized it. But I loved

Neil’s music. Goodness gracious. This guy’s writing…I thought everybody and

their mother was gonna try and start doing his songs. I knew he was a

songwriter. Some of the tunes were movies. They were scripts. To me, Neil was

like another (Bob) Dylan. That’s what he reminded me of. He could do Dylan but

I think he did Dylan his way. It was Neil Young. It wasn’t Bob Dylan.

“Look, I’ve

been on dates with Elvis (Presley) and (Frank) Sinatra. Guys who would arrive

with an entourage. Neil would show up by himself. You have to realize that as

great as a musician and as great as a songwriter he is, Neil would also realize

talent himself. He realized a sound that he liked from a guitar. Neil knew that

the only way to get it was to have that guitar. You’re not gonna get that off a

Tele (Telecaster). You’re not gonna get it off something else. Neil was smart

enough, and most of the good writers and players, if they didn’t have the

acoustic guitar they went to that kind of guitar. Neil liked to experiment. And

he would say, ‘Oh my goodness. Why don’t I do that?’ And he had the wherewithal

and had the time. He had the time to take his time. ‘Wow. That’s a real nice

sound. I like this. I don’t like that.’

“Neil was

smart enough to know what he wanted and knew how to get it. And, Neil had Ahmet

Ertegun in his corner. I think, and we discussed this before, Ahmet had some of

the music publishing. Ahmet encouraged the guys in Buffalo Springfield to write

and do demos at Gold Star. I lived at Gold Star throughout the entire sixties.

Ahmet and Nesuhi were two of the smartest people in the record business. They

almost signed me to Atlantic.

“I opened

the Baked Potato (jazz nightclub) in Studio City on November 17, 1970. We’re

still open. Neil came opening night and would later in the seventies or

eighties would come to the club. I think he was sweet on one of the waitresses.

You gotta remember: In our hallway and on the walls, opposite the men and

women’s bathroom were the answering service phones for all the musicians ‘cause

they were there all the time. They could call Arlyn’s or Your Girl for messages

and get their dates. And everyone hung out there at the beginning.

“Neil once

had an idea and he called me on the telephone. ‘I got an idea. I’m tired of the

band.’ I said ‘Bullshit. You’re tired of the band.’ ‘No. It’s just gonna be me

and you.’ And I said, ‘You’re kidding! Great idea. Let’s do it.’ That was the

last time I heard that. (laughs).”

Henry

Diltz: For their Buffalo

Springfield Again back cover, Stephen called me one day and said, ‘Hey. I’d

like you to write out this list of names that inspired us in your calligraphy

handwriting. People we want to thank.’

I’m in there as Tad Diltz, my old name.”

Kirk

Silsbee: And the album that has an Eve Babitz collage on the

front cover and Diltz’s lettering on the back cover. I like the fact that the

art director at Atlantic had the sense to step back and put his hands up. ‘No.

This is a west coast product. It’s not going to look like every other Atco

album with the second-hand Milton Glasser illustrations. No. we’re gonna do

something different.’”

November saw the release of Buffalo Springfield Again, a defining

moment in L.A. music history; like Brian Wilson before them, the Springfield meshed

song craft with new recording techniques, elevating the music to a rarefied

state of eloquence.

Daniel

Weizmann (Author): Sweet, lilting, and

hypnotic, ‘Rock and Roll Woman’ by Stephen Stills was based on a jam session he

had with Byrd-man David Crosby. Rumor has it that it's an ode to Jefferson

Airplane's Grace Slick. True or not, the character he portrays was ultra-fresh

in '67--a free-spirited woman that is not a fan or a muse. She herself has total rock and roll

agency.

“For my money, ‘Mr. Soul’ is about

Dylan--whether or not Neil Young intended it that way. Young wrote it in five

minutes at the UCLA Medical Center where he was recovering from a bad epilepsy

episode. The dark clown / icon on a bad trip death wish, lost in the hall of

mirrors that is fame channels the Man Behind the Shades, and delivers a tragic

flipside to the bright comedy of the Byrds' ‘So You Wanna Be a Rock and Roll

Star.’ All over the "Satisfaction" riff turned inside-out no less.

“But both ‘Rock and Roll Woman’ and ‘Mr.

Soul’ illustrate how Buffalo Springfield rep a new self-conscious

sophistication, a kind of ‘meta-rock’ energy never before seen.

“Earlier L.A. bands like the Byrds, Love,

and the Standells exposed their secret innocence with every move--even when

they were mugging blue-steel looks for the camera, Stones-style. Some of those

bands contained members that looked like they'd wandered in straight from the

local soda fountain. Even the Doors seem like a happy accident of youth at

times, pink-cheeked college kids jamming jazz on summer break.

“Buffalo Springfield on the other hand

came out of the box seasoned, almost a pre-super group. Many

members had been around the block, had flopped out at Monkees auditions and

paid bar band dues. They enlisted Sonny & Cher's management team and could

pull off a full-force live show. Who else could play a complex jam like

"Bluebird"--a pop-soul-folk blowout with acid rock frenzy, Gabor

Szabo-style meanderings, and dense harmonies, all cascading into an Appalachian

banjo denouement? They were almost like the last soldiers standing on the

Sunset Strip, and their composure was ahead

of its time, the birth of rustic rock royalty.”

Mark

Guerrero: “Blue Bird”- a great rocker with folk

overtones that features a fantastic vocal and acoustic guitar solo by Stills

and rocking electric guitar solos by Neil and Stephen. When played live they would extend the song

with longer solos and rock the house.

‘Hung Upside Down’- a great song about being down and confused that

features Richie Furay singing the slow verses with his incredibly smooth and

clean voice and Stills coming in on the choruses at his rocking best. Here were two of the best singers going in

rock in their primes singing lead on the same track.

“‘Rock and

Roll Woman’ shows Stills at his best as a singer and songwriter. It features a repeating acoustic double stop

guitar lick that’s joined by a three-part vocal harmony doing the same figure

that becomes the background to Stills’ edgy lead vocal. It’s a one of a kind song that also has great

instrumental sections that typify the Buffalo Springfield’s unique style.

“I saw a

riveting live performance of ‘Rock and Roll Woman’ at Cal State Los Angeles in

1967. It was a show stopper. During this

period, I had a band called The Men from S.O.U.N.D who was very popular in East

Los Angeles. We regularly played ‘Mr.

Soul,’ ‘Rock and Roll Woman,’ ‘Hung Upside Down,’ and ‘Bluebird,’ which we

would extend to 20 minutes or a half an hour at times. We absolutely loved doing these songs.”

Kirk Silsbee: There was nothing

like ‘Expecting to Fly' at the time, even within the Beatles' canon. It’s

rubato, without a set tempo. We hadn't heard anything like this in a pop

context. Neil had an odd voice, and though we'd heard him sing, this tune

brought out a ghostly side of him with that floating/spacey intimate as

material.”

“‘Broken Arrow' was Neil’s SMiLE. The

self-referential obsession found in ‘Broken Arrow’ wasn't something

we were used to hearing from these musicians--not just the Springfield but all

of the musicians in the genre who were laying themselves open to examination.

Dylan talked about other people and he crawled up their asses with

microscopes. But he didn’t talk about himself. Then Neil Young

laid himself open, rolled up his sleeves, showed his tracks marks the way Miles

Davis did on ‘It Never Entered My Mind.’ Neil wasn't afraid to show himself

as vulnerable, or scared on Jack Nitzsche's sonic highway. But

the orchestration has Nitzsche responding to the words and the spare

chords that Neil gave him.”

Little

Steven Van Zandt: I saw Buffalo Springfield [November

1967] at a college here [in New York] with the Youngbloods and the Soul

Survivors. It was a great show.”

During spring 1968, Buffalo Springfield were

trapped in what looked to be a scene right out of the 1961 episode of The Twilight Zone Rod Sterling and team

had written. Five Characters in Search of

an Exit, based on a theme from a Luigi Pirandello play, Six Characters in Search of an Author

and Jean- Paul Sarte’s No Exit.

Dickie

Davis: Going on tour with the Buffalo was getting together.

By that time we hardly spoke to each other while we were in town. When we were

on the road everybody started playing together and going to each other’s rooms

and working on songs and being friends again. And we tightened up. One of the

reasons I think that Neil left the band at one point was because he didn’t want

to go back on tour to get tight with them again. Because if that happened in

town we drifted apart. On tour we became friends again.”

And on May 5,

1968, Buffalo Springfield voluntarily fled from their stage stable and became a

mythical fable.

James Cushing: As far as Buffalo Springfield breaking up after

the last show in Long Beach California, I was so into their music I was into

denial they had broken up. Or I figured it was just a temporary re-arrangement.

They were all alive and still living in town. I wasn’t sitting shiva for

Buffalo Springfield. I was waiting for some local deejay one late night to

announce their reformation.”

“The Buffalo

Springfield just sort of snuck UP on everybody,” summarized drummer/writer Paul

Body in a 2018 email. “From ’66 until they shattered like glass, they were

everywhere or seemed to be.

“Saw them

open for the Stones in the Summer of ’66. All fringe and cowboy hats. I seem to

remember them doing ‘Nowadays, Clancy Can’t Even Sing.’ Saw them at the Whisky

with the Daily Flash opening for them. They were just part of that magic

Summer. By the time ’67 rolled around the first album was out and then there

was that little riot on the Sunset Strip that the Springfield immortalized in

‘For What It’s Worth.’ Saw them at the Monterey International Pop Festival and

they were pretty good. The long version of ‘Bluebird’ was played all Summer.

For some reason that version wasn't put on the album.

“It was a

great look into the future, a future that never came because by ’68, there was

a drug bust and they went their separate ways. For about 2 years, there was a

Buffalo Springfield Stampede and then the flame was gone. For two years they

were as good as it got to be.”

On July 30, 1968, Last Time Around, a posthumous album by Buffalo

Springfield that was recorded February-May of ’68, materialized. When Last Time

Around came out in July 1968, the band members were in the midst of

transitioning to new projects: Stills famously joined David Crosby and Graham

Nash in CSN; Young went solo; and Furay started Poco with Jim Messina, who

produced Last Time Around and played bass on two of the songs.

Richie Furay: And

always remember Bruce Palmer’s bass playing. What an interesting melodic bass

player. Only played the notes he had to play.

Dewey Martin our drummer. I got

him ‘Good Time Boy’ so he wouldn’t have to do ‘Midnight Hour.’”

Pete

Johnson in The Los Angeles Times

praised the platter: “Within the Springfield were three of the best pop

songwriters, singers, and guitarists to be found in any American rock group. I

have never seen a group use three guitars as tastefully as they do, weaving a

finely detailed fabric whose pattern never blurred from overlapping.”

“In the short three year

life span of the Buffalo Springfield, Last Time Around was

their last piece of original work--their swan song as the title so-implies,”

offered Gene Aguilera, East L.A. music historian and author (Latino Boxing

in Southern California and Mexican American Boxing in Los

Angeles).

“Well-known for their ego battles, subtle

clues in the LP's art work gives a glimpse into their break-up. A

pronounced crack on the front cover separates Neil Young from the rest of the

group; though on this final LP, Neil penned two of his finest

works: ‘I Am a Child’ and

the opener ‘On The Way Home.’

The back cover further shows the group's fragile state, as individual band

member photos are cut-out to form a fractured montage; and a snippet of a Los Angeles Times article on the

Springfield's Topanga Canyon drug bust delivers the band's final eulogy.

“By the time of the album's release,

original bass player Bruce Palmer was gone; enter Jim Messina (formerly of surf

band Jim Messina & His Jesters; later of Poco) to serve as Buffalo

Springfield's producer, recording engineer, and bass player. Adding

to the wounds, a bizarre contest by local radio station KHJ-AM for listeners to

submit their poetry to be used as lyrics for a new Springfield song became the

opening track of side two, ‘The

Hour of Not Quite Rain.’

“All was not lost in the delivery though, as the Springfield broke up

releasing their most beautiful and compelling album yet (containing such gems

as ‘Kind Woman,’ ‘On The Way

Home,’ ‘Pretty Girl Why’); at the same time curtailing Richie

Furay's rise as a writer, singer, and performer within the band.

“Soon

after, my hair was getting good in the back as I walked the streets of East

L.A. wearing thrift store plaid cowboy shirts in a living testament to one of

my favorite albums and groups.”

Richie

Furay: Everything happened so fast. We were young. We were

new. When we did a six week house band stint at The Whisky we thought we had no

competition. It’s pretty incredible, isn’t it? Five young guys who brought five

different elements together. When we put out stuff together, it was like

‘here’s what I want to contribute to your song, Stephen and Neil.’ We took elements of folk, blues, and country

and we established our own sound. We were pioneers, and I see that.

“As far as

Buffalo Springfield’s catalog, why it still reaches people, I guess it has to

be the songs. Buffalo Springfield was very eclectic. I mean, we reached into so

many genres. Look, the original five

members of Buffalo Springfield couldn’t be replaced. There were nine people out of the Springfield

in two years. Jimmy Messina came in late in the game and did a fine job. I

worked with him on Last Time Around.

“I think

we’re one of the most popular, mysterious American bands. The mystique has

lasted for some reason. Two years, a

monster anthem hit of the ‘60s, but no one really knew us. Neil has gone on to

become an icon, Stephen has made enormous contributions, CS&N, and look at

me into Poco, which I believe opened the doors for the contemporary country

rock sound. Our legacy speaks for itself.”

Stampede by Buffalo Springfield

(Courtesy of Rodney Bingenheimer)

"Neil Young: Heart of Gold" by Harvey Kubernik

Thrasher's Wheat just recently published two highly popular articles by Harvey Kubernik:

Harvey Kubernik is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972. Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For 2021 they are writing a multi-narrative book on Jimi Hendrix for the same publisher.

Otherworld Cottage Industries in July 2020 has just published Harvey’s 508-page book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters, featuring Kubernik interviews with D.A. Pennebaker, Albert Maysles, Murray Lerner, Morgan Neville, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Andrew Loog Oldham, John Ridley, Curtis Hanson, Dick Clark, Travis Pike, Allan Arkush, and David Leaf, among others.

In 1966 and ’67 Harvey Kubernik saw Buffalo Springfield in two of their Southern California concerts and attended debut Neil Young solo concerts in the region.

UK-based Palazzo Editions arranged Harvey’s music and recording study, an illustrated history book, Neil Young, Heart of Gold published in 2015, by Hal Leonard (US), Omnibus Press (UK), Monte Publishing (Canada), and Hardie Grant (Australia), coinciding with Young’s 70th birthday. A German edition was published in 2016.

In 2020 Harvey served as Consultant on Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time documentary directed by Alison Ellwood which debuted om May 2020 on the EPIX/MGM television channel. It was just nominated for Three Emmy nominations.

Harvey served as Consulting Producer on the 2010 singer-songwriter documentary, Troubadours directed by Morgan Neville. The film screened at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival in the documentary category. PBS-TV broadcast the movie in their American Masters series.

Harvey Kubernik, Henry Diltz and Gary Strobl collaborated with ABC-TV in 2013 for their Emmy-winning one hour Eye on L.A. Legends of Laurel Canyon hosted by Tina Malave.

Kubernik’s writings are in several book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski. He was the project coordinator of the recording set The Jack Kerouac Collection.

Kubernik has just penned a back cover book jacket endorsement for author Michael Posner’s book on Leonard Cohen that Simon & Schuster, Canada, will be publishing this fall 2020, Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years).

Deja Vu Photo Composites

Deja Vu Photo Composites

via Susan Miller

Interview w/ Author Harvey Kubernik on Neil Young Turns 70

Labels: album, buffalo springfield, review

Human Highway

Human Highway

Concert Review of the Moment

Concert Review of the Moment

This Land is My Land

This Land is My Land

FREEDOM In A New Year

FREEDOM In A New Year

*Thanks Neil!*

*Thanks Neil!*

![[EFC Blue Ribbon - Free Speech Online]](http://www.thrasherswheat.org/gifs/free-speech.gif)

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young Pardon My Heart

Pardon My Heart

"We're The Ones

"We're The Ones  Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

This blog

This blog

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

What's So Funny About

What's So Funny About