ESSAY: "NEIL YOUNG, WELCOME SOUTH BROTHER" by Jeff Cochran

Here is a guest essay by Jeff Cochran chronicling the strange, intriguing, quintessential, quixotic, and quirky career of Neil Young.

ESSAY: "NEIL YOUNG, WELCOME SOUTH BROTHER"

by Jeff Cochran

Anyone who has followed Neil Young’s career knows him to be spontaneous, unpredictable and quick to change direction. To some degree, that has hampered him artistically as well as commercially. To a larger degree, it has made his career fascinating.

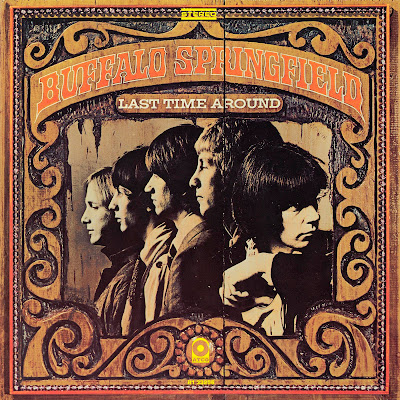

Neil Young, a native of Winnipeg, first captured interest among rock fans in 1966 as a lead guitarist, singer and songwriter with Buffalo Springfield. It wasn’t until the second of Buffalo Springfield’s three albums, however, that Young gained equal footing with band mates Stephen Stills and Richie Furay. Then as the band recorded its third and final album, Last Time Around, Young was on his way out the door. A promising solo career awaited.

His first album, Neil Young, had a couple of rockers but the mood overall was more introspective and romantic than the follow-up, Everybody Knows This is Nowhere. While the first album evoked the aura of “Out of My Mind,” “Broken Arrow,” and “Expecting to Fly,” Young’s softer selections from the Buffalo Springfield catalog, the second album, featuring Young’s new band Crazy Horse, called to mind his “Mr. Soul,” one of Buffalo Springfield’s all-out rockers.

In the meantime, just after the release of Everybody Knows This is Nowhere, Young hooked up once again with Stills, who had formed a new band, one of the first of the so-called “super groups,” with David Crosby and Graham Nash. Crosby, Stills and Nash had just released a wildly successful first album featuring the hits, “Suite Judy Blue Eyes” and “Marrakech Express.” It was 1969, the year of Woodstock and men walking on the moon. Young joined Crosby, Stills and Nash on stage at the Woodstock Festival, leading to great expectations for the album due for release the next year.

Deja Vu Photo Composites

(see 50th Anniversary of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's "Deja Vu" by Harvey Kubernik)

The album, Déjà Vu, is considered top-drawer by many, but some selections are overwrought or cute. Young did contribute the sweet and mournful “Helpless” as well as “Country Girl” and “Everybody I Love You,” co-written with Stills. There were also concert appearances by CSNY across the country, resulting in the live two-record set, Four Way Street. The title was appropriate. The group could blend beautifully and determinedly at times, but there were four separate agendas and none more separate and captivating than Young’s.

Young’s agenda was on full display some 8 months before the release of Four Way Street. His third album, After the Gold Rush, released on August 31, 1970, was immediately deemed a classic. The initial enthusiasm for the album has not only held but increased over the last 52 years. Rock critic Robert Christgau called the album “a rarity, pleasant and hard at the same time.”

Members of Crazy Horse played on After the Gold Rush as did other musicians. Nils Lofgren, better known for his guitar work, played a haunting piano, giving the album a deep and dark dramatic flair. Lofgren’s contributions were pivotal. Instinctively, he perceived the aura Young sought, and enabled listeners to absorb it, as many of the album’s songs carried listeners on a journey to life’s darker places, destinations where lost love, dashed hopes, environmental peril, and violence encroach.

Filming "Journey Through The Past"

Columbus, GA - October 1972

photo by Joel Bernstein

via Neil Young Archives

One violent outpost is visited in “Southern Man.” This song, along with “When You Dance I Can Really Love,” is one of the album’s two rockers. However, “When You Dance…” rocks in a way that connects with the desire expressed in the song. The musicians play with joyful determination similar to that of “Cinnamon Girl,” the opening track on Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere. But “Southern Man” rocks with a sense of foreboding and the terror found in the Deep South in the ’60s. It is not happy rock and roll.

"Now your crosses are burning fast

southern man"

The scenarios in the song recall the malice of fire-hosings in Birmingham. Young, harking back to the days of slavery, sings of the tall white mansions and little shacks, imploring the Southern Man to compensate Blacks for what they’ve endured, before and after slavery. He scathes the hypocrisy of the Southern Man, who believes in what the “good book says,” but doesn’t recognize the humanity in certain creatures of God. In the song’s second verse, the Southern Man rails at a white woman who has a “black man comin’ round.” And he swears he will “cut him down.” Young had previously explored the menacing demons that can overwhelm people, but never so emphatically. The anger possessing Young is akin to one who witnesses such cruelties daily and has grown tired of his own silence in the face of continuing injustice. Even though the prolific Young has recorded dozens of great songs since, “Southern Man” still deserves paramount attention for its dramatic tone and steadfast resolve.

The story of the song goes beyond the song itself, however. There’s the response to the song. That is, the response of people who heard the song or heard about it. Many Southerners have long taken umbrage at outsiders pointing out the sins of their region, particularly sins regarding race. They believe the news media keeps the matter of racial discrimination front and center. Even those whose families would’ve never owned a slave in the 19th century or those who’d sit contentedly next to a Black person on the bus in more contemporary times prefer the subject closed. They know it’s a shameful piece of history that hits close to home. The white man with the kind heart and a special empathy for his Black neighbors also recalls his own family members whose spirits were not so generous. There were family members who discriminated and even those who profited by keeping blacks down. The family members were wrong but they are beloved family members, and since family supposedly trumps all, it hurts when the subject is raised since they, by now, believe it properly settled.

Generous to a fault they may seem, they don’t take into account that their own discomfort with the issue hardly equates to what victims of the racial divide suffered. They might also overlook their own present wealth and comfort, perhaps derived from prejudice against the weak empowered by governmental complicity in the several generations before. They didn’t hold the whips or the ropes or have a voice in the laws allowing repression but many among us have gained materially from the old injustices. If they’d acknowledge as much, it would be a positive step.

Granted, those Southerners didn’t want someone from up North, north of the United States in particular, to chastise their neighbors and loved ones in such a brutally explicit way, even in song. After all, they had read of the bad treatment Dr. Martin Luther King received in Chicago. Therefore, it was reasoned, a Northerner could hardly be the one to judge. To them it seemed Neil Young, a long-haired rock and roller from Canada, was disparaging all white Southerners.

‘SOUTHERN MAN’ by Neil Young

State Theatre, Minneapolis, MN - January 29, 2019 (3M/POLAR VORTEX TOUR)

via Neil Young Archives

It likely got under a white Southerner’s skin even more when his teenagers were listening to “Southern Man,” and while a bit hesitant to say so, the kids knew Neil Young was right and they were glad he wrote the song. And they did not know it just yet, but Young would again take on the issue of race in the South. Not only that, but there would be rejoinders from emerging Southern rockers with their own take on the matter. The teenagers could acknowledge that rock music was tackling serious subjects. Then too, they would say, Neil Young plays an awesome guitar on “Southern Man.”

More To The Picture Than Meets The Eye . . . During the Civil War, Atlanta, Georgia was considered the workshop and warehouse of the Confederacy. As Sherman left it in flames, Atlanta’s fall led to President Lincoln’s reelection and a Union victory.

A century later, Atlanta came to be known as the “Cradle of the Civil Rights Movement.” Martin Luther King, Jr. was born in Atlanta in 1929 and was buried in his hometown 39 years later, a martyr to the cause of Civil Rights, one who paid the ultimate price for the dignity of all men and women. Not every Atlantan bought into the spirit of the civil rights movement, but overall, the city has served as a shining example of how Blacks and whites in government and business can work together, a perfect example being Atlanta’s successful efforts to host the 1996 Olympics.

So Atlanta, a blue city in a red state, seemed natural for a CSNY concert appearance during their 2006 Freedom of Speech tour. Atlanta had welcomed the world in ’96 and had generally* been a successful stop for Neil Young, having played the city numerous times since the ’70s, appearing at the Omni, the Fox Theatre, Philips Arena and the amphitheatres.

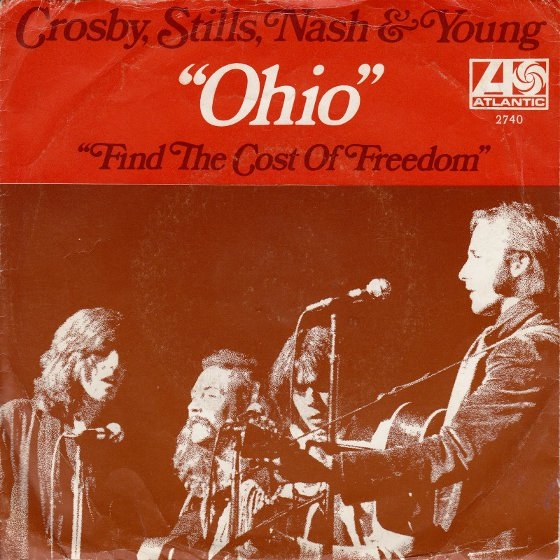

Touring behind Young’s album, Living With War, the reunited CSNY were again striking blows against the empire. The set lists throughout the tour included their anti-war songs from the late ’60s and early ’70s such as “Wooden Ships,” “Military Madness.” and “What Are Their Names,” augmenting Young’s new songs which denounced the United States’ invasion of Iraq. Other well-known sociopolitical songs featured in the concerts were “Teach Your Children,” “Find The Cost Of Freedom” and “For What It’s Worth,” each long embraced by those to the left of America’s political center.

In the early to mid ’80s, it was a more politically conservative Neil Young speaking out on the issues of his adopted country, voicing disapproval over Jimmy Carter and endorsing Ronald Reagan’s arms policies. Young’s comments, however, made their way into the music press when a string of lackluster albums brought his career to a low ebb. Only his hard-core fans, quite use to his mercurial inclinations, took note of the jingoism then influencing his political thoughts. In the late ’80s, when Young revived his career, he also seemed to shift away from the political right, as indicated by the material on his album, Freedom. Absorbing the American mood after Ronald Reagan’s two terms as president, Young noted a country riding high in the material world but unable to secure equanimity of spirit. His observations were key in making Freedom one of his most resonant and vital albums.

"Ohio" 45 Atlantic Records Single (w/ "Find The Cost of Freedom")

by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young - May 1970

As with the Kent State killings which inspired him to write “Ohio,” the most fiery protest song of the rock era, and the discriminatory treatment of blacks in the South which led to his writing “Southern Man” and “Alabama,” it is when Young is most incensed about war, bigotry and misuse of government power that he throws himself head-first into writing and promoting his political songs. The war in Iraq, and especially the way President Bush led his nation into battle, with unfounded claims of Iraq’s “weapons of mass destruction,” and the Mission Accomplished appearance when at least 3,900 more American soldiers were yet to die in the war, were among the things incensing Young in the new century’s first decade. Those things also upset millions of Americans, many who set aside a good chunk of the week’s grocery budget to see Young, with Crosby, Stills and Nash, musically inveigh against the war that was eating away at America. Young assertively promoted the Freedom of Speech tour and Living With War with a special online site that went beyond hawking the musical endeavors. Mainly, he took strong issue over what appeared a betrayal by the people, who, as David Crosby put it, are “the men who really run this land.”

Yes, there was a lot out there regarding the songs featured in the Freedom of Speech tour as well as the assumed political leanings of CSNY. So how was it that hundreds of people who paid their way into Atlanta’s Philips Arena to see the group on August 10, 2006 had such little idea of what was driving the group, particularly Young? And why, if they chose to go to a concert highlighting freedom of speech, were they so hostile when that freedom was exercised? They may have paid more than $100.00 a ticket to see the concert, but they held back on the southern hospitality, seeming to demand a higher cost for freedom of speech and appearing ridiculous all the while.

In his film about the Freedom of Speech tour, CSNY/Déjà Vu, director Neil Young (using the alias Bernard Shakey) does a superlative job in not only covering the tour, but also examining the anguish suffered by those who fought in the Iraq War as well as the anger felt by millions of Americans helping to foot the bill for a war they opposed. President George W. Bush, who led the US into a war of choice, is mocked in the film for his decisions and a bumptious attitude exhibited that’s inappropriate, given the troubles afflicting the nation.

Crosby Stills Nash & Young - 7/6/2006 - Camden, NJ

photo by Buzz Person (via CSNY.net)

The anger felt toward Bush was palpable across America, but in the minds of hundreds who attended the Atlanta Freedom of Speech concert, the president was due a free pass. Never mind all the mistakes he made in office, they thought a rock singer such as Neil Young had some nerve accusing the president of lying. When CSNY broke into “Let’s Impeach the President” from Living With War near the end of the show, many at Philips Arena stood to cheer the sentiment. Also standing, but not in approval, were those who booed the song and Young, giving him, the band and the cameras the finger. Hundreds walked out, as was their right, and, before the cameras, utilized their “freedom of speech,” with some asinine and obscene suggestions directed at Young. There were others, who kept it clean, but indicated a lack of understanding about the meaning of free speech, especially when it’s unpopular.

Southern Man Don’t Need Him Around . . . One gentleman, noting the vast amount of Southerners killed in the Iraq War, said,”You don’t come to the South singing this kind of stuff and springing it on somebody.” Another opinion, albeit less thoughtful, came from a man on the concourse, who determined that, “If you’ve never been shot at or never had to shoot at anyone, then you have no right to blame the government, because they’re … they’re smarter people up there. You may not realize it, but they’re smarter than you.” The poor guy probably has no idea, but his words make him sound as one who, in the words of the song, “Living With War,” would “bow to the laws of the thought police.”

The more circumspect of the people who walked out of Philips Arena that night would have done well to consider Young’s message as one critical of Bush, yet loyal to the nation, and especially those in uniform. President Bush wasn’t forthcoming in justifying America’s invasion of Iraq. He wasn’t loyal to the American people, taking advantage of them while they yearned for leadership after the 9/11 attacks. It seems a hazy memory now, but in the wake of 9/11, millions of Americans set aside partisan politics to support and hope the best for George W. Bush. The people were afraid of what would happen when the other shoe dropped, many of them unaware of how the Bush Administration would gain more power while misleading them.

All of the charges Neil Young made against George W. Bush in “Let’s Impeach The President,” which so angered many Atlanta concert-goers that evening, wouldn’t have gone very far in Washington’s corridors of power. Sadly, many of those in the legislative bodies, whose views came to more closely match Young’s than the Bush Administration’s, had granted approval for America’s invasion of Iraq. They too, if their consciences remain intact, will live with war every day.

Street Survivors by Lynyrd Skynyrd

Ronnie Van Zant wearing a Neil Young "Tonight's the Night" album cover t-shirt

When You Write Your Songs . . . Years ago a prominent reviewer, genuinely fond of Neil Young, wrote that Young’s voice and guitar could often be grating to some listeners. Well, yes. Sometimes Young’s singing and playing are rough, but often there’s beauty in his aggressive style. He certainly can shock some of his more casual listeners. The man who sang sweetly of looking in both Hollywood and Redwood for a heart of gold one year later sang grimly but energetically about “14 junkies too weak to work.” Neil Young covers a lot of ground; he surprises, shocks and challenges his listeners, sometimes to the point, like with many in Atlanta in 2006, they walk out in anger. Yet less than three years later, a line formed around a prestigious Atlanta venue to see Neil Young in concert. The great ones not only entertain, they intrigue.

*The 2003 Atlanta appearance at Chastain Amphitheatre in which songs from the “Greendale” were featured was not well-received. Atlanta amphitheater attendees are not concept album types.

Ronnie Van Zant with Neil Young "Tonight's The Night" T-shirt

Oakland Coliseum, July 2, 1977 - Photo by Michael Zagaris

Neil Young with Lynyrd Skynyrd/Jack Daniels Whiskey T-Shirt

Verona, Italy 7.9.1982 - Photo by Paolo Brillo on Flickr

Thanks for sharing with us here @ TW, Jeff! Much appreciated and very interesting food for thought here on one of our very favorite subjects: the duality of the southern thing.

Looking forward to more words here on Neil.

Until next time, see previously published writing by Jeff Cochran on 50 Years Ago: “Four Dead In Ohio”, which documented the various intersections of Neil Young and President Richard M. Nixon.

Labels: neil young, southern man

Human Highway

Human Highway

Concert Review of the Moment

Concert Review of the Moment

This Land is My Land

This Land is My Land

FREEDOM In A New Year

FREEDOM In A New Year

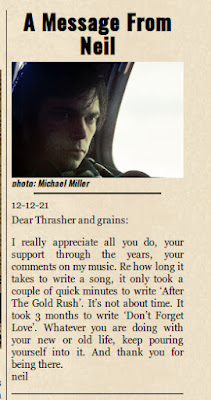

*Thanks Neil!*

*Thanks Neil!*

![[EFC Blue Ribbon - Free Speech Online]](http://www.thrasherswheat.org/gifs/free-speech.gif)

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young Pardon My Heart

Pardon My Heart

"We're The Ones

"We're The Ones  Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

This blog

This blog

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

What's So Funny About

What's So Funny About

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home