Buffalo Springfield Debut LP Released December 1966 (Click photo to enlarge) Here is a comprehensive, in-depth look

back at Buffalo Springfield's debut album, released in December 1966, by Harvey Kubernik.

In 1966 and ’67 Harvey Kubernik saw Buffalo Springfield in two of their

Southern California concerts and attended debut Neil Young solo concerts in the

region.

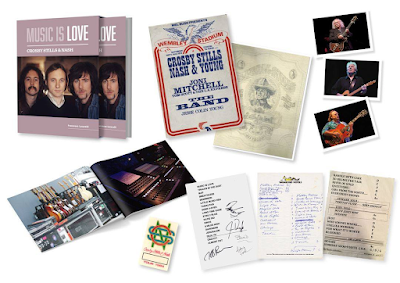

Thrasher's Wheat just recently published several highly popular articles by Harvey Kubernik:

Buffalo Springfield Debut LP Released December 1966

By Harvey Kubernik, Copyright

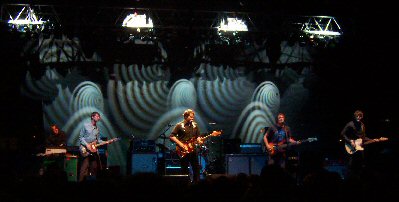

Buffalo Springfield - Third Eye, Oct 1966

In December 1966 I purchased a mono copy of Buffalo Springfield in Hollywood at Wallachs Music City on Sunset and Vine. I witnessed Buffalo Springfield. Twice. In December 1966 with my brother Kenny at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, and in April 1967 inside the Hollywood Bowl.

It was in the spring 1966, when Neil Young and Bruce Palmer hit the road, blazing behind the wheel of a 1953 Pontiac hearse, natch. Finally, in early April ‘66 they arrived in Los Angeles, in search of Stephen Stills and musical dreams held desperately dear.

Coincidentally, Stills had been anxious for Neil to join him as well. Richie Furay, another gypsy, was back with Stills, the promise of a band his inducement to come west.

Where was Neil? Having given up their search for the mercurial Stills, Neil and Bruce decided to head to San Francisco and what sounded like a promising music scene.

In one of the most fortuitous encounters in the history of pop music on that April afternoon on Sunset Boulevard which saw our two protagonists come to a traffic stop at the exact same moment—one going east and the other going west. But, good heavens, who else but Neil would be driving a hearse with Canadian license plates in Los Angeles? And thus, one of the enduring creation myths was born.

Los Angeles, the city of noir, city of night, and city of light. For all its enticing charms—the vaguely toxic vermillion sky, the lustrous undertow of the adjacent Pacific—it could induce a palpable ambivalence.

By 1966, the city was undergoing a vivid reimaging, like a film set readying itself for its next call to “action.” The Watts riots of August 1965 had slapped the dreamy denizens into social/political consciousness, the smog-shrouded basin taking on an acrid, burnt-brown hue.

There was, indeed, something definitely happenin’ here, something best documented in melodies and words of young troubadours who found in pop music the ideal platform to address all those roiling, inchoate concerns. Los Angeles was the epicenter of this sonic youth-quake. The strum of a D minor chord, the hurt in an orphaned voice, a transformative backbeat, a pulsing bass line, the sting of a lead guitar, this was the recipe for rebellion with a bullet, turning protest into publishing.

In my 2016 book, Neil Young: Heart of Gold, I spoke with Dickie Davis, omnipresent Buffalo Springfield advocate, road manager turned guiding force, about his essential contributions to the band.

Stephen Stills @ Gold Star Recording Studio 1966

photo by Henry Diltz

“I met Stephen Stills when he was in the Au Go Go Singers in Houston. In 1966 I was now working at Doug Weston’s Troubadour in Hollywood selling tickets and running the Hoot nights. Neil Young and Bruce Palmer come into town and I hear about it. Stephen and Richie connect with a drummer, Billy Mundi. They were good. I’m watching Steve, Richie, Bruce, with Billy Mundi, and at this point their manager Barry Friedman asked me to help out with the band. Sort of like a road manager thing. Dewey Martin joined as drummer replacing Billy.

“Returning from the Troubadour, in my faded red 1963 Volvo P1800, Richie and I pulled to the curb on Fountain Avenue outside Barry Friedman’s place. I stopped immediately behind a steam roller and noticed a small metal sign hanging loosely from it.

“How about that?” I said. ‘I’ve heard of Mercedes-Benz, and Alfa Romeo, but there’s a Buffalo Springfield. Never heard of that one before.’

“Everyone laughed and got out of the car. We proceeded to try to get the sign off the roller. It was hanging from only one bolt but it wouldn’t come loose. As they went inside, I drove away. Later, possibly the next day, I was at Barry’s. Stephen showed me the sign and said he’d decided that it was the name of the group. I liked the idea. It had a contemporary, sort of Jefferson Airplane ring.”

In my 2009 book, Canyon of Dreams The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon, Laurel Canyon resident, the multi-instrumentalist Van Dyke Parks, who was on the scene at a 1966 Buffalo Springfield practice on Fountain Avenue, emphasized his role suggesting naming rights of the band who never became a brand.

“I said, ‘This is the name of your group. Come out here and look.’ The boys were having an argument and I was so bored I went outside to have a smoke and I saw the grader (road-building tractor) that was in front of Stephen Stills’ rented apartment on Fountain Avenue. The street was being widened, and there was a sign on the grader. It said ‘Buffalo Springfield.’ I pointed it out to them. ‘This is it.’ That was no problem. And of course, they forgot because they were blinded by their own ambitions. They had no idea I came up with that.”

Dickie Davis

Dickie Davis: In later years I heard many times that Van Dyke Parks was crediting himself with thinking of the name. He even said as much to me recently. I was politely skeptical — and silent — until I realized that I had no idea what happened between the time Richie went inside and Stephen’s showing me the sign. He (Stephen) could well have been inside Barry’s at the time they managed to remove the sign and would have been as unaware of my presence as I was of his. It’s just conjecture, but it’s an explanation. (Stephen) never mentioned Van Dyke Parks.

I liked the idea. It had a contemporary, sorta Jefferson Airplanish sound with strong All American/western implication. And, as they say, the rest is history — the kind that’s written.”

Rehearsals with the Buffalo Springfield and Neil Young. My first impression. Neil seemed shy. He seemed anxious to please and he seemed like he really knew how to play guitar. He played maybe a very Chet Atkins country style rock ’n’ roll but if asked he could adapt his playing. If someone said, ‘Give a surf run, Neil,’ he would do it like the Ventures. Nothing to it.

We’d all hang out at Canter’s Delicatessen on Fairfax Avenue after the Whisky a Go Go shows and Ollie Hammond’s on La Cienega.

There was magic at the rehearsals. I was immediately sold. Barry Friedman had seen it grow. I helped it happen at the first gig at the Troubadour. It took so long to set the amplifiers up the audience had lost interest. And it took them a while to get the audience back. But they did. There was a good reaction.”

Richie Furay @ Gold Star Recording Studio 1966

photo by Henry Diltz

Richie Furay: Everything happened so fast. We were young. We were new. When we did a six-week house band stint at The Whisky we thought we had no competition. It’s pretty incredible, isn’t it? Five young guys who brought five different elements together. When we put out stuff together, it was like ‘here’s what I want to contribute to your song, Stephen and Neil.’ We took elements of folk, blues, and country and we established our own sound.

It was the Byrds’ Chris Hillman who got Buffalo Springfield their first Whisky A Go Go booking, which secured a future residency at the venue during May-June 1966.

Buffalo Springfield @ Gold Star Recording Studio 1966

photo by Henry Diltz

Read more »Labels: album, buffalo springfield, neil young, review, richie furay, stephen stills

Human Highway

Human Highway

Concert Review of the Moment

Concert Review of the Moment

This Land is My Land

This Land is My Land

FREEDOM In A New Year

FREEDOM In A New Year

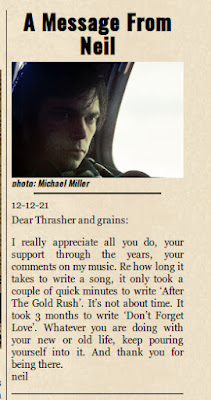

*Thanks Neil!*

*Thanks Neil!*

![[EFC Blue Ribbon - Free Speech Online]](http://www.thrasherswheat.org/gifs/free-speech.gif)

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young Pardon My Heart

Pardon My Heart

"We're The Ones

"We're The Ones  Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

This blog

This blog

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

What's So Funny About

What's So Funny About

Given the insight added by the Harvest Time quote regarding Alabama, the song can be seen in, if not a brand new light, a more complex one, where it is elevated above its status of Southern Man II. It seems like the self-referential lines begin to incorporate more nods to Southern and country culture as the verses add up.

At first, the subject is primarily Neil himself, dropping minor allusions to keep that country tone going (“the devil fools with…” “swing low,”) as he expresses his personal feelings at the end of March ‘71 [NYA manuscript caption]. “You got the spare change, you got to feel strange” is his ambivalent mood about being a “rich hippie.” “And now the moment is all that it meant” sounds like a critique of a hippieism itself. In the original manuscript, Neil put the word “moment” in quotes, tellingly.

Where Southern Man was a straightforward social commentary and political statement, Alabama is a metacognitive meditation, a critique/questioning of self.

Here the singer sings to himself, playfully naming himself “Alabama.” He recognizes that he is affecting an American style, all the while an outsider. This perspective will be developed in a later line, so let’s look at that chorus first. Rusties will recognize the references to self right out the gate. “…weight on your shoulders that’s breaking your back,” was written between Neil’s major back injury and the resultant surgery. We know he was in physical pain during this time and would hardly stand up with an electric guitar until months later.

“Your Cadillac has got a wheel in the ditch and a wheel on the track.” Know anyone with a fondness for big old cars and ditches? [note: The first Caddy I could find in Special Deluxe was the limo he bought in ‘74 when he and Zeke were on the road with the CSNY tour.]

The next verse names Alabama as the person/subject and, separately, as the place itself (“broken glass windows down in Alabama”) The irony of banjos playing through these broken windows but that also “take you down home” speaks to the personal conflict already established and connects it to the character’s namesake state. The chorus returns, reinforcing the pain and strife of the singer/his subject. The final verse brings back Neil’s discomfort with fame living in the States. “Oh Alabama, can I see you and shake your hand?” is followed by the wry “make friends down in Alabama.” These lines bring to mind Neil’s comment in Harvest Time regarding his new famous life, where people’s eyes don’t look right when they talk to him. [Again sorry for the lack of direct quotes, I’m paraphrasing from memory of the screening last weekend.]

“I’m from a new land, I come to you and see all this ruin, what are you doing?” Another enigmatic line, but following the lyrics above, it seems he is stepping out of the Alabama identity and into the world of Southern Man, having established his own voice as full of contradiction and self-doubt. This seems to add the weight of credibility based in humility to the critical observations first laid out with “see the old folks tied in white ropes.” In fact, that particular line can be read not just as “them Southern folk are KKK,” but that they themselves are tied up, bound by the shameful side of their own heritage, unable to change. The ropes themselves are white, after all.

After asking “what are you doing?” Alabama closes with another question: “You got the rest of the union to help you along/ What’s going wrong?” A mere Southern Man retread would have left this line a reaching throwaway. It doesn’t quite make sense posed directly to the state of Alabama. But given a double meaning whose main purpose is an inward questioning, the line lands hard. We can easily see “the rest of the union” as CSN, Crazy Horse, or even the Stray Gators, from all of whom Neil has begun to isolate himself. He knows they support him, so why is he struggling? It’s worth noting that Neil had expected to be finished with Harvest by April [an offhand remark heard in the movie]. Alabama was written on March 30th, 1971 and no more recording was done until September.

When Alabama was penned, it wasn’t quite Harvest Time yet.