"The Musical Transcendence of Neil Young" by author Martin Halliwell

Here is a rather excellent essay by author Martin Halliwell which explores Neil Young’s long-running fascination with dreams.

From The Musical Transcendence of Neil Young by author Martin Halliwell:

Dreams for Young are sometimes a puzzle to solve and at other times a new geography to explore, corresponding to the two dominant dream theories of the 1960s: the Freudian theory in which dreams are a working through of repressed psychic matter; and the existential humanist view of dreams as an alternative topography. Dreaming is rarely a doorway to the state of lost innocence for which Young yearns in “Sugar Mountain,” but it has the capacity to transport the singer and the listener elsewhere. Through the act of dreaming Young can drift purposefully, pulling together sounds, images and colours in creative ways, and can explore the twists and turns of the unconscious where one image blurs with the next. The nature of dreams means that their shape keeps morphing. This can lead the dreamer towards deeper meaning, but can also drift away into impressions and noise. At times Young searches for direction–such as the quest on his 2007 track “Spirit Road” to discover the “long highway” within — and at other times escapes from meaning into a play of imagery and sound.Full excerpt at The Musical Transcendence of Neil Young by author Martin Halliwell.

We can identify this second trend in one of Young’s early dream songs, “Broken Arrow.” This six-minute coda to the second Buffalo Springfield album Buffalo Springfield Again seems to be inspired by the early-summer release of The Beatles’ concept album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, leading Young to incorporate crowd noises from a Beatles concert and the opening distorted snippet of a live performance of “Mr Soul,” sung by drummer Dewey Martin. Despite its musical variety there is little input from the band, except for backing vocals by Richie Furay, added after Young had recorded the song in September 1967. Its power stems from Young’s sound experiments and the visually arresting figure of a Native American standing alone on a riverbank with an empty quiver. This image of the ‘vanishing Indian’ with a broken arrow suggests either surrender to an unstoppable force or an offering of peace. What makes this a mysterious image is that there is no discernible enemy in sight; instead the verses describe a triad of social pressures (fame, adolescence and marriage) as if modern social organization has defeated the nobility of the Native American.

The question “did you see him in the river?” incorporates the listener in a historical story in which nature is replaced by social ritual. This transition is reinforced by the river imagery, which seems more urban than rural and permits the figure no room to flourish. The complex phrasing that Young uses to describe the unarmed Native American is developed in the song’s structure, where forward movement is interrupted by sound snippets: the burst of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” at the end of the first verse, the military drums in the second and the closing lounge jazz suggest that the Native American’s voice is difficult to hear beneath layers of cultural sediment. But the subjects of each verse also find it hard to sustain their stories: the concert audience waits expectantly outside in the rain; the anxious adolescent “hangs up his eyelids” and the king and queen vanish in the midst of a wedding parade. Each new scene takes us back to the haunting image of the Native American with his broken arrow; only the fade-out heartbeat suggests that his spirit survives in the face of debilitating modern forces.

The three parts of “Broken Arrow” constitute probably the most formally arranged track of Young’s career. More often he prefers to work fluidly with themes and sensations that meld into one another, as they do on another three-part song, “Country Girl (Medley),” from CSNY’s Déjà Vu album. Taking a more domestic subject as its focus, the song is nevertheless mythical. It links back to “Broken Arrow” via the short song “Down Down Down,” which he had recorded with Buffalo Springfield but not released. This track has two moods: the first stems from the chorus of “Broken Arrow,” but with the enigmatic Native American replaced by a mysterious woman; the second mood stems from a set of unanswerable questions which Young revisits in “Country Girl.” There are echoes of “Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing” in the singer’s frustrated attempt to see and think clearly, but here the questions cluster around the motives of the female figure who has committed a transgression that seems to require the singer’s forgiveness. We have seen these elements before. The woman in the river is a similar kind of beckoning figure to the “Cowgirl in the Sand” and arouses suspicions that she has been sharing her love around. But in “Down Down Down” it seems as if the singer, too, has been unfaithful or has let her down. The lyric suggests equivalence between the two, but also confusion on behalf of the singer, particularly about the sequence of events, which words have meaning and who is most to blame.

Also, Martin Halliwell's new book is titled Neil Young: American Traveller (Reverb).

For more on Neil Young's dreams, also see:

- "All Those Dreams" by Neil Young from the album Storytone

- Americana and The American Dream

- Review: Neil Young's Dreamin' Man

- Chrome Dreams II Reviews

All in a dream, all in a dream

The loading had begun

Flying mother nature's silver seed

To a new home in the sun

Flying mother nature's silver seed

To a new home

Labels: book, neil young

Human Highway

Human Highway

Concert Review of the Moment

Concert Review of the Moment

This Land is My Land

This Land is My Land

FREEDOM In A New Year

FREEDOM In A New Year

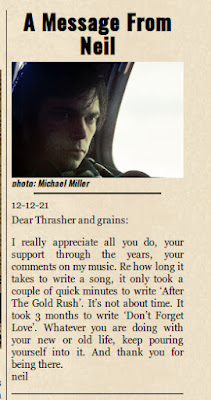

*Thanks Neil!*

*Thanks Neil!*

![[EFC Blue Ribbon - Free Speech Online]](http://www.thrasherswheat.org/gifs/free-speech.gif)

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Neil Young Pardon My Heart

Pardon My Heart

"We're The Ones

"We're The Ones  Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

Thanks for Supporting Thrasher's Wheat!

This blog

This blog

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

(... he didn't kill himself either...)

#AaronDidntKillHimself

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Neil Young's Moon Songs

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism

Civic Duty Is Not Terrorism Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

Orwell (and Grandpa) Was Right

What's So Funny About

What's So Funny About

1 Comments:

That essay really made me listen afresh to Broken Arrow. Great stuff. I'll definitely read the book.

Post a Comment

<< Home